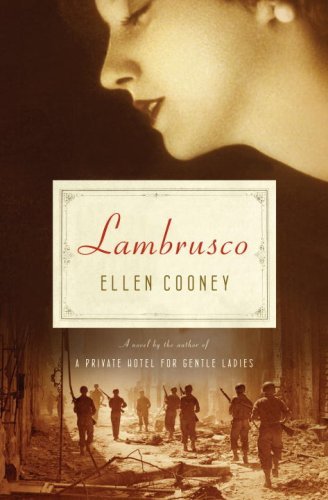

Lambrusco

Lucia Fantini, legendary singer and widow of Aldo, whose village restaurant was her personal stage, secretly helps her son’s resistance movement by smuggling arms in shopping bags. Unfortunately, her son takes matters into his own hands and blows up a German tank, thus also bringing his mother under suspicion.

Enter an American undercover operative, a tall, angular woman named Annmarie who was a professional golfer in peacetime. Disguised as a nun, she alerts Lucia to the danger of returning to her home. But the dangers are nearer than anyone thinks, and Lucia and her friends are inadvertently bombed by the U.S., causing Lucia a head wound that gives her quest to find her son a dreamlike, surreal quality.

It is the strange relationship of Lucia and Annmarie that provides the true crux of the story. Annmarie, on the surface so different from Lucia, becomes her means of finding her way back to herself in the midst of the chaos of war.

Cooney populates her fictional world with colorful and varied characters, but occasionally she overindulges by making them a little too obviously Italianate and melodramatic—perhaps intentionally operatic. She most successfully gives Lucia a distinctive voice in all senses, complete with delirious conversations with the three great Italian opera composers, Rossini, Verdi and Puccini. The story is well constructed and draws one through, but the reader’s sympathy is at times attenuated by scenes that start out amusing or engaging and then continue for too long.

Nonetheless, Lambrusco provides a glimpse of a part of World War II with which many Americans are unfamiliar, and believably illustrates the degree to which opera is part of the fabric of everyday life in war-torn Italy, either by its presence or its absence.