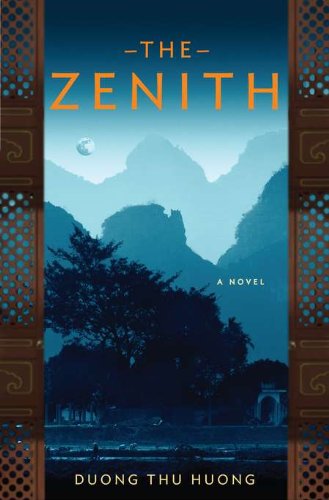

The Zenith

Author Duong Thu Huong’s sweeping book The Zenith opens in 1969 with Ho Chi Minh a temple prisoner of his own regime, of his conscience, and of his memories. “Memory,” he thinks, “is the one who builds you a permanent court of justice.” A man who sacrificed his own life for his people, “Saint Ho” is a figure too important to communist Vietnam to be allowed to be human, too big to fail. That’s something he already did, in the Politburo’s eyes, when he fell in love with a younger woman in the 1950s. He is now consumed by guilt over abandoning her and their children, who were hidden from the regime in adoptive homes after her rape and murder. He sees that his socialist ideals birthed a conscienceless regime that uses him as they would a puppet. He also sees that the revolution’s costs to individual people’s lives and loves have not been repaid in joy or justice.

The book consists of five parts, a back and forth between the chairman and his friend (whose wife adopts a motherless child), a woodcutter whose story reads like a village fable, and “The Unknown Brother-in-Law” who flees from Vietnam’s corruption. The book’s theme is the incompatibility of power and conscience — and the inevitability of power. A linking character throughout is Vietnam itself, lyrically lovely but also tortured.

The Zenith has been aptly compared to Dr. Zhivago, also an adagio suffused with inescapable regret.

This long book is not an easy read. But The Zenith is worth the time and attention, every page revealing richer, deeper treasures, poetic and moving, a grand yet intimate canvas of history, ideology, love affairs, and tragic beauty — most of all beauty, of the country, of the women, and of the heart. Recommended.