The Doll Factory

Iris paints porcelain faces, ‘threads hair through the holes in the scalp, sometimes curls it with irons heated in the coals,’ in Mrs Salter’s Doll Emporium. She longs to escape the drudgery, to learn to paint properly. A few streets away, Silas harbours a comparable ambition. A taxidermist of subtle skill, he runs a middling successful Shop of Curiosities, but is forever ‘hounded by doubts, by the ache for more.’

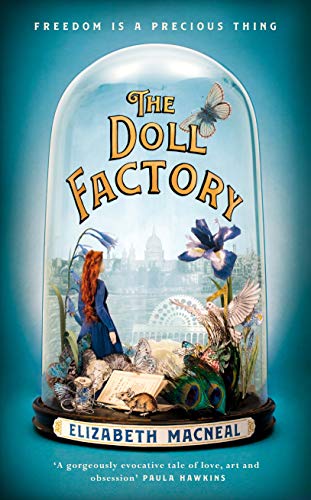

The Doll Factory toys with our reader’s sensibilities from the outset. Looking over Silas’ shoulder we relish each telling detail of Victoriana, but we are conscious all along of our present-day squeam. A dog-skin purse, a fan made of whale’s lung tissue, ‘a pocket of air escapes, gamey, sweet and putrid.’ Elizabeth Macneal is needling us, making us squirm. We have a similarly modern response to Iris. She is an honest girl, ‘so unlike those squawking bonnet touters on Cranbourne Alley,’ but we do not want her to be honest. We want her, like real historical bonnet touter Lizzie Siddal (painter’s muse to the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood) to follow her dream of painting, to shake off her Victorian sensibilities. So we read the story for the thrill of rediscovering a Victorian world, but always interpreting the scenes, aware that we do not want the characters to be Victorian, we want them to break the glass jar.

Elizabeth Macneal’s magnificent debut works on so many different levels. We identify with protagonist Iris. She is flawed and, in her own estimation, a selfish character, but we warm to her because we feel her desperation, and because, wherever she can be, she is kind.

The Doll Factory is not just a satisfying literary novel, it is a love story and a thriller that absolutely gallops to its conclusion. Read it!