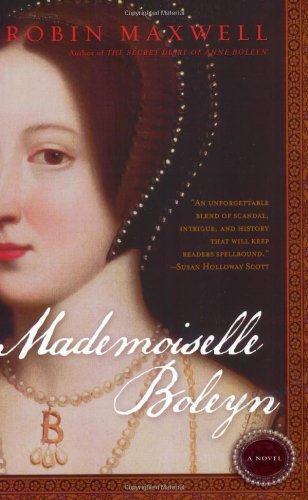

Mademoiselle Boleyn

Robin Maxwell returns to the subject of her debut (The Secret Diary of Anne Boleyn) in this colorful and imaginative novel. Anne Boleyn’s youth in France has hardly been addressed in fiction, compared to her later career as Henry VIII’s most famous and ultimately tragic wife. Nevertheless, many historians believe it was during her stay at the court of François I where Anne, and to a lesser extent her sister, Mary, learned about the perils and power of becoming a royal mistress. Maxwell capitalizes on the ongoing fascination with the Boleyn sisters by plunging us into the licentious, corrupt world of Henry VIII’s French rival—a world where women are treated as little more than chattel to be used for titles and favors most often enjoyed by the men in their lives. As a young girl, Anne is spared the degradations her elder sister endures, as Mary is forced by their own father to seduce François in order to discover the king’s political secrets.

It is here where the novel’s main drawback emerges. While Anne’s voice is clever and clear-headed, in tune with the woman she’ll later become, the sexual abuse visited on Mary challenges the reader to look beyond the graphic language for a hint of that most tempting of Renaissance aphrodisiacs: the quest for status. Though the motive espoused by their father is to spy on the French king, neither sister does much of it. Mary spends her time cruelly sublimated, while Anne befriends the king’s erudite sister Marguerite, and more fancifully, an elderly Leonardo da Vinci, who teaches her the importance of observation and imparts advice on how she might save herself from François’s satiric advances. However, in the end the novel proves compulsive reading as Anne comes to realize she needn’t become a man’s victim in order to triumph.