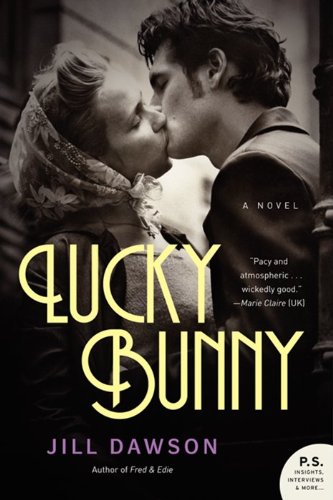

Lucky Bunny

The title of Jill Dawson’s seventh novel, Lucky Bunny, is ironic. The white bunny that Queenie Dove receives as a present from her petty criminal father may represent her innocence, contrasting it against her father’s escapades and her parents’ volatile relationship, but it never gives her the luck to escape from that situation. Instead it becomes a symbol for her lost innocence as she grows into a troubled and incarcerated teen. Even the attention given to Queenie by her grandmother couldn’t reverse the effects of the bad parenting.

This narrative shares much in common with Daniel Defoe’s Moll Flanders, beginning with Queenie, who alludes to the classic 18th-century novel. Like Moll Flanders, Queenie has a cheeky disregard for authority rooted in a tragic and victimized childhood. Beginning with her birth in 1933, Queenie’s story progresses through the starkness of her early childhood to her renaming of herself as “Queenie,” culminating in her rise to criminal fame and fortune in the early Sixties. It isn’t until she has a daughter of her own that Queenie decides to change her lifestyle in order to benefit her daughter, but only after one last job: the 1963 Great Train Robbery.

Dawson’s light, comical writing balances the dark tone of this novel, while her fast pace and the engaging slang Queenie uses amongst her criminal milieu creates a feminist twist on the male gangster story. The characters are interesting, and Queenie’s criminal tendencies never make her unlikeable. Indeed, Queenie Dove comes out on top as a smart, creative, and tough woman who seizes her chance to make a life for herself and her child that is vastly different from the one that ushered Queenie into criminal life.