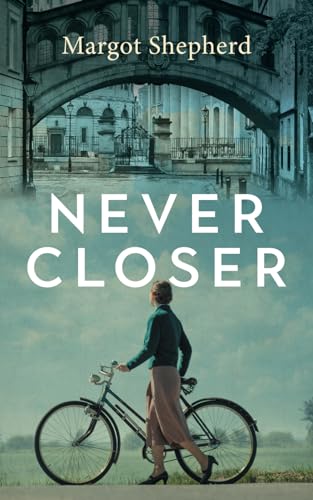

Never Closer

Oxford, 1940: teenaged Alice’s first job is in a laboratory where mould is deliberately grown in a motley collection of bedpans, pie-dishes, and biscuit tins. This is the realm of the scientists Heatley, Chain and Florey, and the mould is penicillin. Alice’s story is told in parallel with Jo’s, in 2017.

Ultimately their two narratives intertwine in this carefully crafted story, starting with Jo finding Alice’s diary in a vintage clothes shop; the discovery offering her a respite from her life with an unreliable, insensitive, and covertly domineering husband. Then she receives an urgent call to the John Radcliffe Hospital (the modern successor to the institution where penicillin was first administered), where her daughter is in a coma with meningitis. In wartime, Alice and her fellow ‘penicillin girls’ scramble frantically to grow more penicillin in an attempt to save the life of a policeman; the leaders of the lab have to cross the Atlantic to find pharma companies prepared to manufacture their discovery. Domestically, Alice worries about her father and a young man met at a dance, both servicemen, while dreaming of a nursing career, and clashing with her cold and unhappy mother.

The stories of these two women are told with empathy and perception. Shepherd’s impeccable research shines through: anaemia as a side effect of the amyl acetate used in extraction; Molyneaux’s rayon utility shirtwaisters; a train journey with no stations identified. Reading Alice’s diary to her convalescing daughter, Jo reminds her that ‘the death rate from infectious diseases in this country is the lowest it’s ever been’ but has a premonition of an impending medical calamity. This is a historical novel for our times, a reminder of how much medical science has bettered our lives.