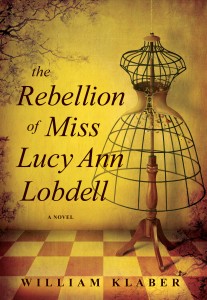

William Klaber’s The Rebellion of Miss Lucy Ann Lobdell and Gender Identity in pre-Civil War America

JANE STEEN

“Lucy wrestled with all kinds of things that didn’t have words back then. And it wasn’t just the lack of vocabulary; Lucy had no guidance. No YouTube or LGBT groups. No Oprah or Ellen.”

In The Rebellion of Miss Lucy Ann Lobdell, William Klaber takes the reader into the mind of a woman trying to live on her own terms, and finding both acceptance and rejection along the way. In an era where same-sex unions are still being challenged, the question of gender identity has been raised by well-received writers like Sarah Waters (Tipping the Velvet) and Emma Donoghue (Frog Music) and it’s interesting to come across a new treatment of gender-bending set in mid-19th century America. This was, after all, a time when the frontier was pushing outward as a society dominated by white males, still challenged by the remnants of a population seen as “other” by the settlers. It’s no coincidence, I believe, that Lucy Lobdell has a strong sympathy for the Native American tribes.

The acceptance shown in the novel by some (by no means all) characters who encounter Lucy Ann Lobdell’s rebellious spirit might be the most surprising challenge to our perceptions of the 19th-century mind, and yet it is based on fact. Klaber refers to newspaper articles where Lucy’s relationship with a woman was sympathetically described, and her 1858 trial for wearing men’s clothing was dismissed because she had violated no state or local laws. Later in Klaber’s novel, Lucy and her wife Marie are helped materially by the woman who loved her as a man before her real gender became widely known.

And yet Lucy, or Joseph as she preferred to be called, could not live in peace either with herself or with her neighbors, and spent the last thirty years of her life in insane asylums without Marie. Even before that, Lucy-Joseph and Marie’s bonding—kept in the public eye along with the memory of the trial by Lucy-Joseph’s talent for getting arrested—was singular enough for the time that it attracted considerable journalistic attention, adding to the burdens borne by a couple who claimed to want to be left alone to live as they wished. Addressing a journalist who had written about the couple in generally considerate terms, Marie—quoted in Klaber’s factual final chapter—seized on the term “strange conduct” to which she retorted, “I do not know why the companionship of two women should be termed ‘strange.’ The opposite sex are often seen in close companionship, and, Mr. Ham, my sex are not inferior to yours.”

William Klaber, who lived in a house connected with Lucy-Joseph, took on the complex task of unfolding her* tale from her own viewpoint after being asked by a local historian to write what was originally intended to be a biography. Applying fiction to history, Klaber told me, was his choice to allow readers “to enter rooms otherwise denied them” by the historical record. Klaber shows Lucy-Joseph—a widow with a child—embarking on her new life as a man as a way to find paying work. She also needed to avoid her only option as a woman, which was to make a distasteful marriage as a means of providing herself and her child with security. “But once Lucy began to pass as a man,” Klaber says, “things began to change. And that’s where the story is—the changes. Lucy didn’t go in search of women, she discovered the attraction only after they became attracted to her. And then she had to make sense of it. And becoming a man was part of how she made sense of it . . . She doesn’t reject being a mother or being a woman so much as she walks a path that goes in only one direction: ‘All I had won by my deceit was some imitation of freedom. Was it a fair trade? I couldn’t say, but I knew one thing for certain—it was irreversible. Having risen, however imperfectly, to the rank of citizen, I could not go back to the indentured world of propriety and deference.’”

William Klaber, who lived in a house connected with Lucy-Joseph, took on the complex task of unfolding her* tale from her own viewpoint after being asked by a local historian to write what was originally intended to be a biography. Applying fiction to history, Klaber told me, was his choice to allow readers “to enter rooms otherwise denied them” by the historical record. Klaber shows Lucy-Joseph—a widow with a child—embarking on her new life as a man as a way to find paying work. She also needed to avoid her only option as a woman, which was to make a distasteful marriage as a means of providing herself and her child with security. “But once Lucy began to pass as a man,” Klaber says, “things began to change. And that’s where the story is—the changes. Lucy didn’t go in search of women, she discovered the attraction only after they became attracted to her. And then she had to make sense of it. And becoming a man was part of how she made sense of it . . . She doesn’t reject being a mother or being a woman so much as she walks a path that goes in only one direction: ‘All I had won by my deceit was some imitation of freedom. Was it a fair trade? I couldn’t say, but I knew one thing for certain—it was irreversible. Having risen, however imperfectly, to the rank of citizen, I could not go back to the indentured world of propriety and deference.’”

Translating Lucy-Joseph’s life into novel form also brought technical challenges. Klaber begins the story at the point where Lucy-Joseph leaves home, disguised fully as a man for the first time, and ends it before her disappearance into the world of the insane asylums. So we are unable to follow her into an environment where she is studied as a case of sexual perversion (giving rise, arguably, to the first use of the word Lesbian to describe woman-to-woman relationships) or see her early life as a hunter who liked to wear her brother’s clothes but willingly entered into a heterosexual marriage. The narrative itself is in two parts, divided by the five or seven years (accounts vary) between the trial and Lucy-Joseph’s reappearance in search of her daughter, during which she lived alone as a hunter. “How,” says Klaber, “can you dramatize five years alone in the woods? You can’t.” And since the thrust of the novel is about Lucy-Joseph’s struggle to live as she wanted within society, I would agree with his choice to omit this period.

All of these complexities are a lot for a novelist to take on, but Klaber focuses on giving Lucy-Joseph her own voice and translating other people’s reactions to her through her eyes. As he says, “Lucy is smart, she is brave, but she is also naïve. She describes things in simple terms. Her thoughts are lean.” She has no labels for herself, and thus as a character she resists our attempts to put labels on her. “There are those already squabbling over whether Lucy was a Lesbian, a transvestite, bi-sexual, or transgender,” says Klaber. “I personally don’t feel the need to fit her into any modern box, but I do think it’s important to remember, and we know this from her early writing, that . . . she was a Feminist, an advocate for women’s rights.” Lucy’s personal narrative is about the freedom to live outside the box into which even the unruly frontier wanted to put her. “When I was young I heard a preacher speak out against the sin of unnatural unions. I didn’t know what those unions were, but a woman loving another woman might surely be one. This troubled me, but not as much as you might suppose. And before I am judged from the far off comfort of a chair, please remember that everything had changed for me. Up was down, red was blue . . . . “

I would like to see a novel based on Lucy-Joseph’s experiences in the asylum, but that would be a completely different novel. What we are allowed to see in The Rebellion of Miss Lucy Ann Lobdell is a becoming, a mind trying to grasp its own identity and build a life in the face of an uncomprehending world.

*Like Mr. Klaber, I refer to Lucy-Joseph by the female pronoun for simplicity’s sake.

About the contributor: Jane Steen was born in England and has lived in three countries, but still manages to hang on to the English accent. She currently resides in the Chicago suburbs with her family, but visits the UK as often as possible. Jane is a self-published author of historical fiction, starting with The House of Closed Doors, the first in a series. She’s also a runner, a knitter and designer of lace shawls, and full-time executive assistant to a cognitively disabled daughter.