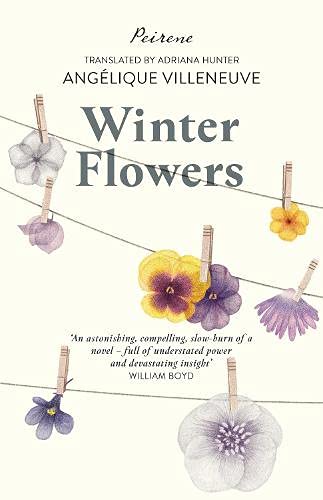

Winter Flowers

Our central character is Jeanne Caillet, whose husband Toussant sustained near-fatal facial injuries in the First World War and has, since then, been confined in a military hospital which specialises in such disfiguring wounds. “I want you not to come,” he tells her by letter and, obedient and loving, Jeanne does as he tells her and does not go, applying herself to the task of keeping her daughter fed.

Jeanne’s great skill is her ability to create exquisite artificial flowers, using silks and satins and velvets, from which she composes sought-after decorations for the hats, corsages, bosoms, waists, dining tables and flower displays of the rich. Although commanding high prices from wealthy clients, the sourcing of materials, plus the endless hours each creation takes to complete, means that the profit from her labours is insufficient, resulting in little money for food or fuel for the stove.

Eventually Toussant is discharged but, unsurprisingly, it is not a homecoming anyone could imagine or wish for. A white mask now covers that part of the face that barely exists any longer, and their reunion is equally distorted by what has happened and is still happening to them.

Wrapped in unremitting poverty and surrounded by characters whose lives are as tragic and hopeless as their own, the little family will struggle on, reforming their own, strangely changed, relationship and raising their child, Leonie/Leo, the five-year-old whose resilience and acceptance of her circumstances is virtually the only positive element in this unashamedly bleak story.

The locations are lightly, convincingly and effectively drawn for us. The construction of the narrative is cinematic in its effective precision.