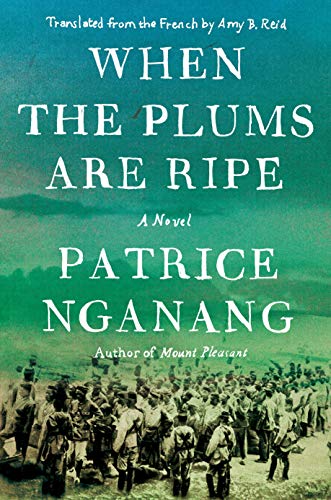

When the Plums Are Ripe

In French colonial Cameroon, 1940, the poet and civil servant Pouka returns to his village. He finds his father, a kind of seer, having visions of Hitler dead by suicide and the townspeople gripped by unease and schadenfreude, “only a German word could express it,” as their colonizers were themselves being torn apart.

Patrice Nganang, a professor of cultural studies and comparative literature at Stony Brook University, primarily tells his tale through Pouka, “the eldest son, the first of some fifty children,” who decides to teach poetry in his village. Other characters and subplots abound, including the women who sell the plums of the title—plums that flood the market during their short season: “sometimes, at the end of the day, they are dumped into piles on the pavement, just like that, a pile of garbage attracting flies.”

At its best, this novel demands to be savored at a slower, more old-fashioned tempo. Nganang’s voice is that of a familiar, confident storyteller. His intellectual narrator has endless, often amusing, asides to his listeners. He ends a chapter titled “The Chiasmatic Enchantments of History” thusly: “But this, clearly, is one of history’s chiasmuses; in time it will be dealt with by Fritz, or maybe Um Nyobè.” The next chapter begins, “In due time, yes, in due time!”

This story of people living within the history and brutal tangles of colonization is more important now than ever, and this book will surely find its way onto reading lists for students of African cultures. However, for me, the author’s ironical style, so evocative of storytellers of centuries past, didn’t work. It removed me from the story rather than beguiling me into the light of a campfire to listen, which was, I think, his intent.