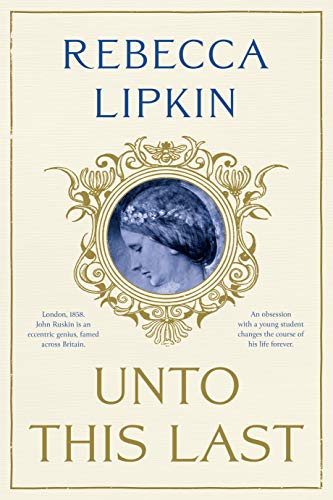

Unto This Last

John Ruskin was approaching forty when he agreed to teach drawing to the nine-year-old Rose La Touche, with whom he gradually fell in love. Lipkin has thoroughly researched their relationship, with some phrases coming straight from Ruskin’s own account. Really this is two books, as halfway through the narrative shifts backwards to recount Ruskin’s disastrous first marriage to Effie Gray and its scandalous annulment.

Lipkin’s is a somewhat overwritten style, with ‘said’ replaced by harrumphed, buoyed, goaded, griped, extolled, retreated, and others. Sentences are sometimes long and the language baroque, as in ‘she forgave herself liberally for feeding on such satiates.’

Ruskin comes across as a self-absorbed, impotent Dr. Casaubon, and Rose an unappealingly precocious zealot. There is little sense of recoil expressed at a man courting a child thirty years his junior, but this is arguably in keeping with the mores of that age: until 1875 the age of consent in England and Wales was 12, and then was raised only to 13. As Rose herself remarks, the marriage market for a girl is ‘no better than being a poor fox in a hunt.’

There are convincing vignettes of Ruskin’s circle, notably of an acerbic Jane Welsh Carlyle, Georgiana Burne-Jones and a young Oscar Wilde. Some inaccuracies jar, as in ‘Rose displayed her fiercely Celtic streak’ (she was Ascendancy, so not Celt) and Ruskin ‘at St Mark’s Square… lingered in the dark cloisters of the cathedral, where… the stained-glass windows cast a glow,’ though St Mark’s has neither a cloister nor stained-glass. That said, Rose’s decline is told with great empathy, and the author’s enthusiasm for her subject is without doubt. The reader will learn much about Ruskin’s life and beliefs.