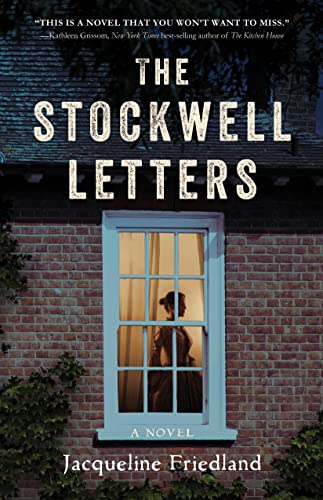

The Stockwell Letters

In 1854, the abolitionist movement in the United States had a cause célèbre: Anthony Burns. Having escaped enslavement in Virginia, Burns was seized in Boston and prosecuted under the Fugitive Slave Act. The Stockwell Letters tells Burns’ story through his own narrative, through that of Ann Phillips, the invalid wife of Boston abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and through that of Colette Randolph, a young married woman in Richmond.

I found the narratives of Burns and Ann Phillips to be the most successful in The Stockwell Letters (which is not an epistolary novel despite the implications of the title, the meaning of which becomes clear late in the book). Burns has a compelling story to tell, and even though Ann Phillips’ illness constrains her actions, it has not broken her spirit or altered her determination to help a cause in which she passionately believes. Colette, a fictitious character, fared less well with me. I found parts of her story implausible—for instance, at the outset of the novel, she’s allowed by her tyrannical, aristocratic husband to take an unpaid teaching job—and her habit of dropping French phrases, with the occasional “y’all” to remind the reader she’s a Southerner, is cloying. It doesn’t help that her husband ticks every box for the stereotypical Historical Bad Guy: rich, married to a much younger woman whom he regards only as his property, obsessed with acquiring a male heir, cruel to his dependents, and physically unappealing. Some nuance would have helped. Aside from that, however, Jacqueline Friedland’s novel is an engrossing, quick read, one that illuminates an episode of history that must not be forgotten.