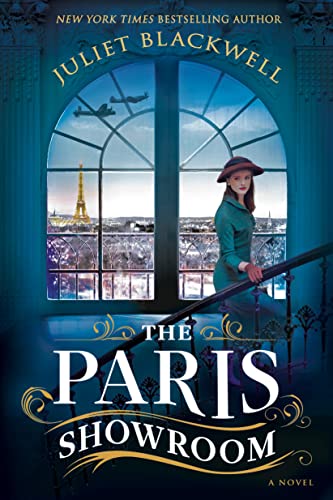

The Paris Showroom

During World War II, the Nazi-allied Vichy regime deported Jews from France to concentration camps while sending other prisoners to forced labor camps within Paris to sort furnishings and other goods stolen from Jewish homes and businesses, part of the Third Reich’s plan to deprive Jews of their property. Juliet Blackwell opens her new novel in one of those labor camps—the Lévitan department store.

Capucine Benoît, a designer of elaborate fans, has been sent there following her arrest on suspicion of being a Communist. Although worried about her deported father, Bruno, and guilty about being estranged from her daughter, Mathilde, Capucine is determined to survive. An acquaintance’s affair with a Nazi officer allows Capucine to parlay her design skills to advantage and negotiate favors in exchange for help decorating the friend’s apartment.

In chapters alternating between Capucine’s first-person and Mathilde’s third-person viewpoints, the novel captures cleavages in France during the Nazi occupation around moral questions dividing families and rupturing friendships, while painting a vivid portrait of what life might have been like for those imprisoned in Paris. Collaborationists, like Capucine’s in-laws, aid the Germans while resistance fighters, like a friend of Mathilde’s, brave mortal danger to support the allies, actions that lead Mathilde to change. Inside the store, friendships form, rituals are sustained, and love blossoms.

Blackwell has done her homework to bring characters and setting alive, evoking not only the Vichy years, but also the interwar years, when people commingled across racial and class lines in the Montmartre jazz clubs, an intermixing later condemned by the Nazis. At times, the research overwhelms the story, giving the impression that the writer tried to pack everything she’d learned—about fans or jazz or Purim—into the narrative, regardless of whether it served the story. Despite some implausible turns of character and a too-neat ending, the novel is entertaining.