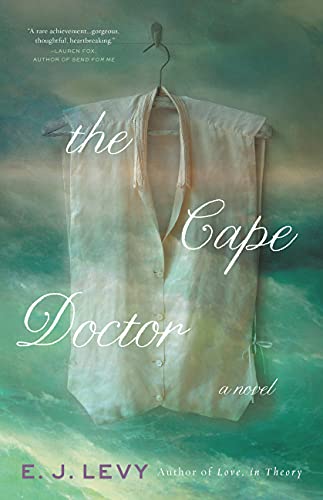

The Cape Doctor

Levy’s dreamlike debut fictionalizes the life of 19th-century Dr. James Miranda Barry, the Irish-born military surgeon who advocated for medical reforms, performed a successful Caesarean section, and was found post-mortem to have been assigned female at birth. In the novel, the dead narrator, named Jonathan Perry, reflects on formative life events, which include early mentorship by General Mirandus, medical school in Edinburgh, and his posting in Cape Town, South Africa, which focuses on Perry’s growing intimacy and ultimately doomed affair with the colony’s governor, here named Lord Charles Somerton.

The liquid, luscious prose is only rarely overwrought, and Perry’s objections to the era’s crude medicine, and the horrors endured by enslaved Africans, are palatable to the modern taste. The novel grapples convincingly with identity themes, but Levy’s ultimate stance on gender doesn’t do full justice to this complex, fascinating figure.

Historians and biographers vary on whether they read Barry as a woman, a trans man, or possibly intersex. The early sections beautifully explore Perry’s gender nonconformity: the death of Margaret Brackley so Jonathan might live; the freedom and authority granted Perry by male garb and manner, and the perplexities of having to hide soiled monthly linens and female breasts. But once Somerton is introduced, the narrator speaks of Perry as a masquerade, a “secret” hidden in plain sight, a disguise of the hidden “truth” of female sex, and a “name” for which the character gives up love, marriage, and maternity. By the end, Levy’s character has become conventional even by 19th-century standards of womanhood.

To some readers, including this one, the choice feels like one more erasure of trans and gender-nonconforming bodies from contemporary view and the historical record. But the novel is still an enchanting story of ambition and loss, a struggle between liberty and convention, and other authors may take up the opportunity that Levy declined.