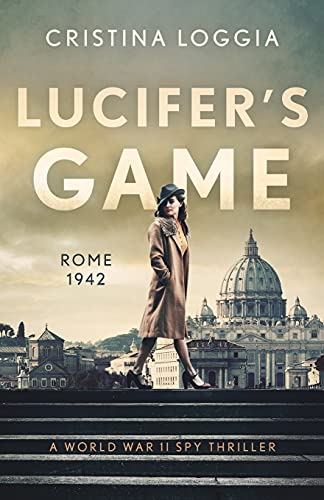

Lucifer’s Game

Rome, 1942. Cordelia Olivieri needs to leave Italy because her Jewish heritage puts her in danger. Father Colombo passes information to the British from inside the neutral Vatican City. Lieutenant-Colonel Friedrich Schaeffer must discover who is giving away details of the German supply convoys to North Africa. Linking them all is the British SOE agent, codenamed Lucifer, operating deep undercover among the Roman Blackshirt squadristi.

Cordelia is drawn into playing “Lucifer’s game” in order to secure her escape, but her growing love for the German officer imperils them both. Throw into the mix a truly devilish villain with his own interest in finding the spy, and a personal vendetta against Schaeffer, and we have the bones of a muscular and dangerous spy thriller told from several unconventional perspectives. The plot is full of twists and jolts, and it did keep me turning the pages.

However, the constant in-scene head-hopping between characters, major and minor, disrupts the flow of the narrative, as do parts of the structure—too many breaks for scene-setting and background detail, along with the complex, flashback-heavy nature of the early chapters.

For much of the narrative, we do not know the name Lucifer is using in Italy—Guido—but we have scenes throughout where he is referred to as Lucifer even when the viewpoint character would know him only as Guido, or just as an anonymous Blackshirt.

Stylistically, the novel can feel at times overwritten. The author makes use of a number of words that jar in the narrative, e.g., discombobulation (p.89), which feels too “comic”; and the heroine’s “impalpable” (flimsy? clingy?) skirt (p.185). Other words such as “telluric” (p. 94), “boutade” (p.121) and “exsiccation” (p. 128) had me reaching for the dictionary. This is a shame because the core of the novel is strong.