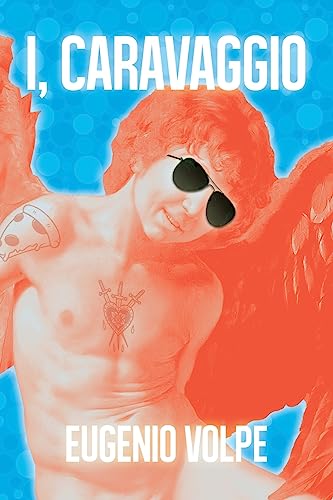

I, Caravaggio

Michelangelo Merisi (1571-1610), known by his birthplace, Caravaggio, was a towering figure in Baroque painting, known for intense, sometimes grotesque psychological realism and dramatic lighting. Eugenio Volpe’s fictive autobiography, I, Caravaggio, links the artist genius and his restive, violent life by positing three personae: “Michelangelo,” street-fighter, poppy-addicted, accused murderer with eclectic sexual tastes; Caravaggio the painter of pious Biblical scenes; and “yours truly,” who tries to connect and pacify the warring personae.

While most historical fiction attempts a semblance of historical diction, Caravaggio speaks of cops, selfies, and images “gone viral.” He’s gobsmacked, he schleps, he paints his sex life in pungent, modern terms. He flaunts the irony of his creative process: prostitutes model his Madonnas and saints, their street price soars, and pimps fume. Cardinals, popes and princes protest, but pay handsomely for his Biblical visions; Caravaggio revels in their hypocrisy—and squanders their pay. His artistic mastery magnificently expands as his personal life and health devolves. I, Caravaggio is rich in complex irony.

Readers may want to look up the paintings Volpe cites and need a rough understanding of papal politics. The multiplicity of characters and their plots and counter-plots are often dizzying. Caravaggio’s personal vendettas, furies, and petty quarrels become tiresomely repetitive, yet deeply pitiable. Ultimately, Michaelangelo, Caravaggio, and “yours truly” cannot endure, and all nearly welcome the inevitable, violent end. Yet great art endures, and I, Caravaggio makes painfully clear the horrific price of its creation.