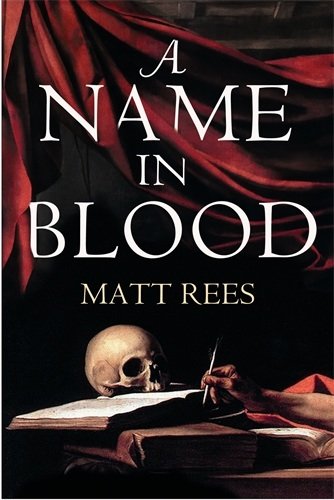

A Name in Blood

The mystery of Caravaggio’s last months and death has never been satisfactorily resolved: traditionally, he is said to have died of malaria, in Porto Ercole, as he desperately sought a way to return to Rome. Rees has invented another entirely plausible version, involving the Knights of Malta to whose ranks Caravaggio was admitted two years before his death. Rees successfully conveys the inner energy and drive of the man who has always been regarded as the roughest diamond in 16th-century Italian art: no suave pastels or verdant landscapes here, but rather the rawness of street life and an unconventional choice of models that sits uncomfortably with the biblical subjects of his paintings. The studied use of light and shade and the artist’s technique for painting lifelike portraits are all carefully described since both were exceptionally innovative at the time.

Yet, as Rees portrays him, Caravaggio was also a man of iron principle whose inner moral compass made him all too aware of the jeopardy facing his soul at the Last Judgement. Redemption was a powerful motivation. Life in Caravaggio’s Rome was dangerous, riven by factions between the ruling families, the Farnese and the Colonna. Caravaggio’s own brilliant artworks attracted high-ranking patrons but also numerous rivals; it was his personal links to the Colonna that eventually led Caravaggio to commit a murder for which he faced the death sentence or exile. The story of the subsequent years, the fate of his true love, Lena, and the events on Malta make a riveting and persuasive read. The only gripe I had was that any author should think twice before including Italian words in dialogue, and above all check for correct syntax and authenticity. However, this was a minor distraction from a novel that would be best read in situ, following in the artist’s tracks and viewing those artworks still in their original settings.