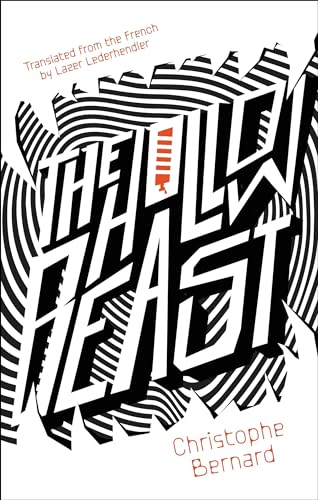

The Hollow Beast (Biblioasis International Translation Series, 46)

In modern Montreal, Quebec, François Bourge abandons his dissertation in favour of writing a book, having decided he alone can untangle the feud between his grandfather, Monti, who caught a hockey puck mid-air between his teeth, and Victor Bradley, referee turned mailman, whose misjudged awarding of the goal to the opposing team provoked a revenge story still alive and well three generations later. Decidedly upset by the unfair ruling in 1911, Monti spends years mailing everything from a tent and compass, along with every conceivable outback supply, to his cabin in the woods, which he at one point dismantles and moves, thus forcing mailman Bradley to trek time and again to unknown parts to complete delivery. Monti, very rich from Klondike gold maybe (or a surreal card game in which four players are simultaneously dealt royal flushes), and magnanimous benefactor of the fictional Saint-Lancelot-de-la-Frayère infrastructure, clearly did something to somebody somewhere, François surmises, as he heads home to the Gaspésie for the first time since leaving.

This absurdist romp through 100 years of distortions of reality is reminiscent of the hallucinogenic madness of Hunter Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, in this case fuelled by Yukon Gold, a bottle of which Monti and his descendants receive in the mail every week, although the contemporary events are equally cocaine-charged. The Kesey-esque post-modernist narrative is ruthlessly bizarre, and so mired in metaphor it taxed the little grey cells to extremes to make connections over 600 dense pages. Several references are so very Québécois, many won’t make them at all. With synapses popping and sparking and sometimes shorting out, the scepticism and disillusionment heard through Bernard’s words, though darkly amusing in places, underpins serious themes. This pop-culture stream-of-consciousness writing has some distasteful scenes (accurately portrayed), some lucidly penetrable, and some suffering word insanity, but overall displays the originality expected of great art.