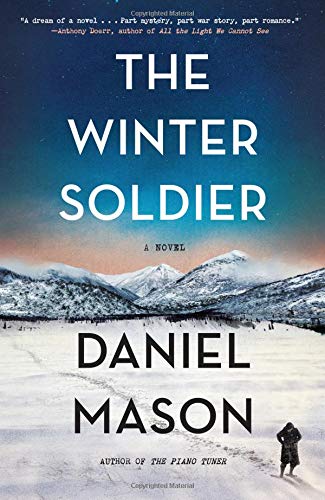

The Winter Soldier

In 1915, war sends Lucius Krzelewski, a third-year Polish medical student, to a regimental hospital somewhere on the Polish front. He’s the only doctor, aided by a single nurse and three orderlies, and they toil inside a dark, dank, freezing church whose roof has a large hole in it. But his interior inadequacies matter more, for his training consisted entirely of rote memorization, and now he must amputate limbs.

However, Sister Margarete, the nurse, is there to teach him, and he proves a quick study, though not always quick enough to escape her sardonic commentary. She belongs to the Order of Saint Catherine of Siena, speaks about lice in biblical phrases, and has been known to withhold painkillers from patients who trespass certain boundaries. Nevertheless, the socially inept Lucius manages to talk to her; therein hangs a tale.

Mason, who teaches psychiatry, portrays psychological trauma with a stripped-down authenticity I’ve never read anywhere else. Likewise, his depictions of incompetence, class-consciousness, bitter ethnic rivalry, and utter disarray within the Austro-Hungarian Army ring absolutely true. The hospital scenes, though gory (be warned) are exceptionally gripping, for only through the intense cruelty, pain, and heartache can Lucius see his shortcomings and capacities.

My only quibbles concern the beautifully written though overly long section about Lucius’s background, as if Mason feels he must prove why his protagonist can’t talk about anything except medicine, and a seemingly implausible occurrence toward the end. But The Winter Soldier offers an unusual tale of romance and coming of age, set against an equally unusual portrayal of war. Readers looking for history rendered vividly will be transported, as will those of literary bent. The Winter Soldier is magnificent.