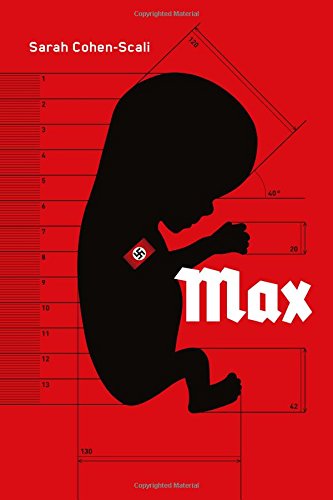

Max

April 20, 1936, on the Führer’s birthday, our preternaturally cognizant hero is born to a blond-haired, blue-eyed mother who has given her fertility to copulate with an SS-officer she doesn’t know to help create the master race in a Nazi program called Lebensborn. His measurements are perfect, strong and large; so is his coloring. Shortly, as soon as he is weaned, he will begin the intense physical and mental training that will turn him into the perfect servant of the Third Reich, the only family he will ever know.

In first person, Konrad, whose mother prefers the name Max, hits all the actual events that might affect a child until the United Nations program rescues him, after the fall of Berlin to the Soviets in 1945. Crude, boyish humor gets no improvement by Nazi indoctrination and prejudice. It’s hard to like this guy who lures blond-haired, blue-eyed Polish children away from their families for “Germanization” to correct the mistakes of birth, who calmly talks his less-than-perfect peers onto trains bound for Auschwitz. One boy he condemns to the same life as his own is a secret Polish Jew he eventually claims as a brother.

How anyone could return to “normal” after such a childhood is a wonder, and the more interesting question that we never get to explore. The young German women who offer themselves to the Lebensborn program are rationed a few paragraphs of personal consideration, the Polish mothers less. While this is a new take on the old story, I did not find it helped me to a better understanding of humanity. In our annual glut of Holocaust recreations, I think there are better choices to be found than this otherwise competent translation from the French.