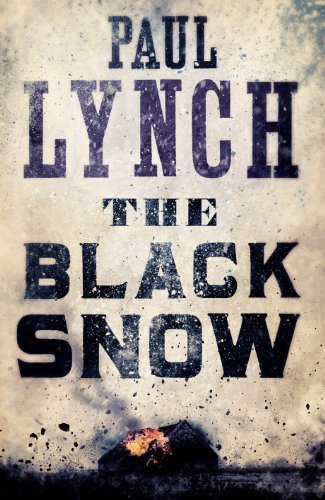

The Black Snow

In rural Ireland, in the spring of 1945, with the war in Europe a distant echo barely disturbing the steady routine of farming life, labourer Matthew Peoples runs into a burning byre in an attempt to save the cattle, and does not come out alive. Farmer Barnabas Kane, himself barely escaping death, is powerless to intervene. Following the disaster, as Barnabas and his family are compelled to rely on their neighbours for help, rifts and prejudices are exposed in the community, and the Kane family’s efforts at recovery are threatened.

This is a beautifully observed subversion of the rural novel, which calmly and ruthlessly demolishes the traditions of the form. There is much to admire, particularly in Lynch’s astutely poetic observations of weather and landscape, and his lacerating exposure of the small cruelties of a community closing against those perceived as outsiders with ideas above their station. At his best, Lynch can nail a mood or a moment with devastating acuity.

However, although I felt I should admire this novel even if I couldn’t quite love it, in the final analysis I found it disappointing. Much has been made of Lynch’s poetic language and original voice, but while these sometimes lead to vivid and memorable prose, more often than not they leave the reader with the sense of an author trying too hard. In his efforts to achieve a poetic prose, Lynch sometimes produces sentences so convoluted, so burdened by an excess of word reversals, that I needed to read them several times to get the sense of them, which frustrated and distracted me. Furthermore, the denouement is so dark it descends into melodrama and is hard to take seriously.