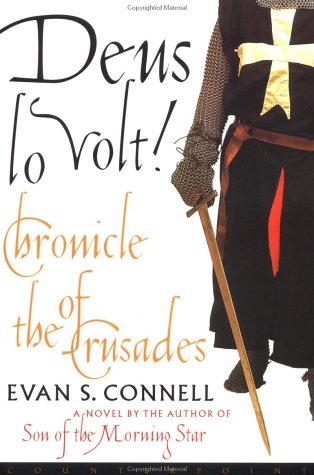

Deus Lo Volt! Chronicle of the Crusades

We are transported by author Evan S. Connell to the two centuries of human existence – from 1095 to 1289 – more enmired in the blood of Christians and Saracens than any other period known to humankind. From 1095, when Pope Urban sounded the call to glory for the liberation of Jerusalem, hundreds of thousands of Christians took the cross and marched forth – to lands unknown, to fears inconceivable, to ultimate defeat at the hands of the non-believers. Their rallying cry over those 200 years was the same – Deus Lo Volt! – God Wills It! How culturally disparate Christians banded together to try to defeat those who did not believe in Jesus Christ is the stuff of this complex work, a book which Connell himself states is not an historical novel, but rather, a book about the Crusades.

Certainly, we learn more about the Crusades than a novelist would feel compelled to communicate, yet this is not a work of non-fiction. The first 360 pages of the book are nothing more or less than a recital of every historical event from every historical source – letters, chronicles and other medieval documents – containing even a passing mention of a Crusade-related event. We meet the famous and infamous. Connell provides interesting personal information about such warriors as Richard Lionheart, Tancred, Bohemond, Saladin and finally, King Louis, whose presence permeates the last one hundred pages of the narrative. Connell’s research is so impeccable and so extensive that it dehumanizes what should have been easily made human, making the book unbearably tedious. Nor would I feel comfortable recommending Deus Lo Volt! as a source-book for Crusades studies, since it is imprecise as a purely historical account.

The narrator of this complex volume is one Jean de Joinville, whose ancestors fought in the earlier Crusades. Jean, the seneschal of King Louis and his devoted friend and servant, is an interesting fellow – unfortunate because we don’t get to meet Jean and understand his role until the book is three-fourths done. In the first part of the book, Jean is merely the instrument iterating various monologues and dialogues of the earlier Crusaders, and telling of historical events where someone or other “gave up the ghost” or “ascended to glory.” (This becomes a torturously over-used phrase in the book.) Jean has no real presence, and there is no character development whatsoever, until the later historical events which involve the pious Louis.

Despite the amazing scope of Connell’s research, it was a dreadful chore for me to get through the first 360 pages of the book. Where there are so many fine examples of Crusades-related historical fiction available, I recommend leaving this one unread.