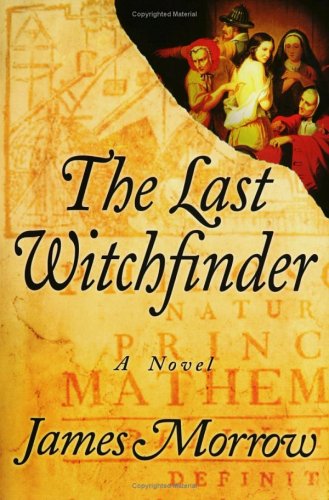

The Last Witchfinder

Jennet Stearne’s childhood wasn’t typical, but it was happy, or at least it began that way. Her home life morally focused on her family’s commitment to the eradication of sorcery, with Jennet’s father as witchfinder and her Aunt Isobel as philosopher and scientist. When Isobel’s experiments make it appear she could be practicing the occult, she is tried and sentenced to death as a witch. She entreats Jennet to formulate an argumentum grande to refute the Parliamentary Witchcraft Act of 1604 and prevent the future torture of innocent souls.

Set largely between 1688 and 1725, The Last Witchfinder follows Jennet’s search for this logical argument, from Salem, to a Nimacook village, to Philadelphia, then back to Philadelphia again via London and a not-so-deserted island. The promise made to her aunt shapes Jennet’s life, just as the pursuit of Cleansing comes to define her brother’s existence. Along the way she finds time marry an Indian brave, then a postman, and to have an intellectual and passionate relationship with a certain young printer, Ben Franklin.

Even as James Morrow’s main character points out the impossibility of the existence of witches, the author conveys the subtle parallels between aspects of the natural laws of science and the (perceived) demonic world. How easy it must have been for strongly devout people to believe in – and fear – the existence of unholy spirits.

An unlikely device is Morrow’s inspired choice of narrators: Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica. It’s a tribute to the author’s narrative strength that he can make the notion of one book authoring another an intriguing possibility, one that’s no more implausible than witchcraft itself. A fascinating and compelling book.