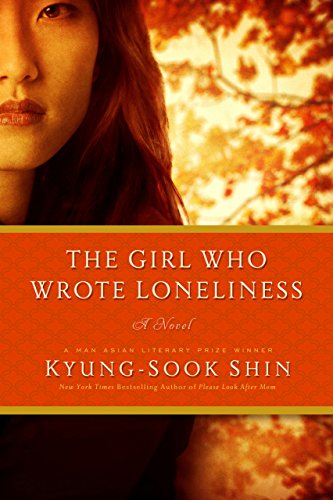

The Girl Who Wrote Loneliness

Our narrator writes and writes, attempting to understand how the past weaves into the present and, yes, even the future. Aware that she has a problem with escaping or running away, she attempts to find a place where she can reflect on what happened in South Korea from the 1970s to the mid-1990s. A former high school student accuses her, stating, “You don’t seem to write about us. Your life seems different from ours now.” The narrator is shamed and even haunted by these simple words.

So begins the story of this older Korean writer analyzing life as a student, industrial worker, and writer. A secondary, subtle thread is the question of what distinguishes a fictional novel from a work of “literature.” Nature provides the only comforting, hopeful image, “seeing beautiful birds asleep with their faces toward the sky.” Newly formed unions are deemed the enemy, and the state believes that the Special Education Program for Industrial Workers, also known as industrial warriors, is what will jettison the post-WWII impoverished country into a prosperous future. The assassination of President Park Chung-hee is given a romantic aura as well, which is shocking to any intelligent reader. Little by little we realize we are reading about a country with a socialist government that very much resembles a dictatorship on the national and local levels. “I am on the threshold of a home being crushed and torn apart.”

The tone is as dreary as its topic, but it is a fictional account of what absolutely must be told and known. Intense but revealing historical fiction that the author calls something between “not quite fact, not quite fiction.”