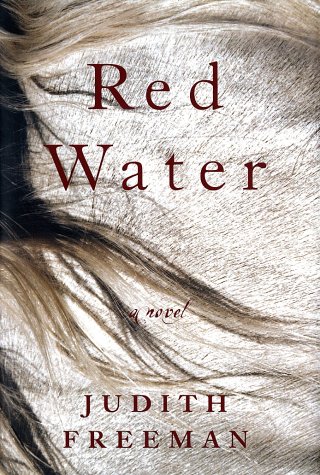

Red Water

The Mountain Meadows Massacre continues to blight Mormon history today, as the church recently used its might to put a halt to excavations on the site when the first child’s skull with a bullet hole in it was found. In 1857 a band of settlers, 120 men, women and children, had the misfortune to pass through Mormon territory, what is now southern Utah, on their way to California. Here they were massacred, save a few youngsters who were later adopted into Mormon households. Mormons blamed the local natives, but other evidence eventually led to the execution of a leader of the church in the region, John D. Lee. Still further evidence suggests Lee died as a scapegoat to divert attention from where the orders really originated–church headquarters in Salt Lake, the Prophet Brigham Young himself.

This is the backdrop against which Freeman weaves her tale. She has a wonderful flair for describing the bleak, gritty Southern Utah landscape where water runs blood-red with iron-rich mud. She has made the bold choice to tell the tale from the point of view of three of Lee’s eighteen wives who found him, generally, a man worth sharing. This gives a well-rounded picture of the ripple effects of the terrible deed so no one is completely all black or all white. The scene where one of the meadows’ orphans sees unsuspecting wife Emma, proud in a new dress given her by her husband, and cries: “That’s my mama’s dress. What have you done with my mama?” is a masterstroke.

At some points I felt cheated when the narrative led me into over-worn tropes of the western genre. Even if the hunter is a woman, the chase after horse thieves is still pretty much a chase after horse thieves. And I did wish for a closer glimpse into Lee’s mind, longed for a telling of the massacre’s actual events by their participants as they happened, not years later by wives who, in two cases, weren’t even married to the man in 1857. But this novel was not the place for that. Maybe that is a place so dark that fiction cannot go.