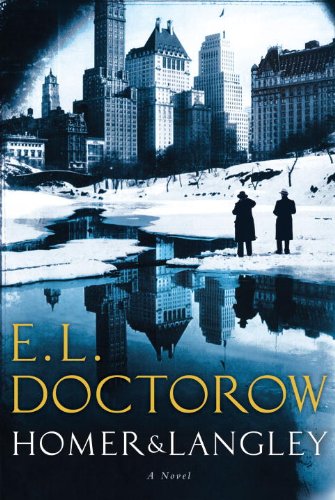

Homer & Langley

For a review suited to this journal, it is well to begin by pointing out that the novel is not, and does not claim to be, an entirely factual biography of the Collyer brothers, who lived out their lives in a dark and decaying New York mansion surrounded by 130 tons of junk and old newspapers. (Interested readers may consult Wikipedia and other Google citations for the authentic background. For instance, the brothers, in fact, died in 1947 although Doctorow has them living on into the 1970s.)

But departures from fact should deter no one from relishing this fascinating meditation on the human condition. The story is narrated by Homer, the blind brother—appropriately a blind singer of tales, although his canvas is not epic but miniature. Through his words, we see the two young men, popular and sociable in the beginning, gradually retreat into eccentricity, reclusiveness, misanthropy, turning their parents’ luxurious home into a rat’s nest, a lonely fortress, and ultimately into a tomb.

Homer and Langley have been diagnosed posthumously as victims of obsessive-compulsive disorder, but Doctorow invests their condition with the trappings of a cockeyed philosophy. Thus, Langley collects newspapers by the ton in an effort to reduce all the world’s news items to their Platonic forms, which he will publish in a universal newspaper valid for all time. And Homer’s narrative voice, ever tolerant, sensitive, and affectionate, works a kind of magic on this craziness, drawing us into their solipsistic world until the abnormal begins to seem eerily normal.

Unlike the author’s Ragtime or The March, this small book tells a very small story, but one that is wonderfully imagined, deeply felt, and wise.