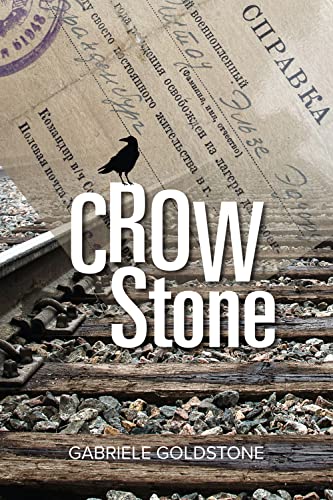

Crow Stone

Throughout human history, women have been the victors’ spoils of war. Revenge is a factor, but more to the point, it’s easy for soldiers to victimize defenseless women and girls.

In Crow Stone, Goldstone draws on her mother’s experience for the story of Katya, a victim of politics from the aftermath of the Russian Revolution to her final liberation in 1947. Born in Ukraine to a minor landowner who resisted collectivization, Katya and her family are sent to a Siberian work camp where some happy childhood moments lighten years of bitter exile. Eventually the remains of her family settle in East Prussia.

Katya’s barely German and is certainly not a Nazi, but when Hitler’s regime falls, she’s “the enemy” to invading Soviet troops. A forced march east to the Ural Mountains begins. Chapter after chapter describes the conditions: starvation and thirst, frostbite, stumbling barefoot for days, physical abuse, rape, typhus, suffocation in cattle cars, the dead tossed aside, twelve-hour shifts in coal mines, being driven like animals and tormented by lice and fleas.

With stunning fortitude and a few strokes of luck, Katya survives, her spirit nearly intact. This in itself is a miracle, an astonishing testament to the human spirit. For the reader, though, the unrelieved accounting of abuse becomes hard to bear. Reduced to constant struggle for survival, personalities flatten, and Katya’s companions blend together. The Soviet guards divide into bad and less bad, drunk and less drunk.

Clearly this is a piece of history which must be known, but Crow Stone becomes less a novel than an unflinching account of the horrors of war.