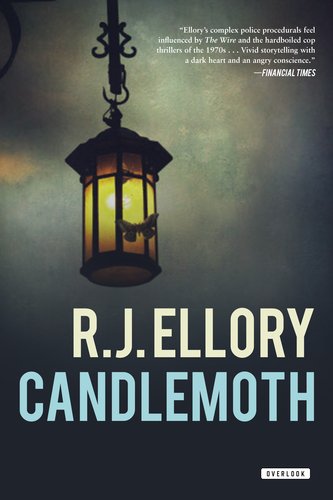

Candlemoth

I approached Candlemoth with some apprehension. Its framing device is the story of a man on Death Row in 1982, recounting to a sympathetic priest how he was convicted of the murder of his best friend. Flashbacks fill in the details; Daniel Ford and Nathan Verney became friends when they were six years old. Not so remarkable except for the fact that Daniel is white and Nathan black, and the time was 1952 in South Carolina. Nathan is the leader in this friendship, so when he receives his draft notice to Vietnam, he convinces Daniel to go on the run with him. Their flight ends when they return to their hometown and Nathan is murdered.

That stark description may explain my inward sigh on reading the book jacket. The “wrongfully convicted man” trope seemed like a painful read. Instead of tiresome clichés, however, I found an engrossing story of friendship in a particularly challenging time. Daniel and Nathan’s bond was continually tested, not only by outside pressures like race relations and the war but by their own personalities. Daniel was in the position of being painfully aware of his shortcomings—hindsight helped as he told his story to Father Rousseau—and as the last one standing in this friendship, there is poignancy in his regret for the things left undone.

There is a twist at the end, but I would hesitate to call this a murder mystery. The conclusion, although redemptive, felt almost immaterial to me. What captured me were the two boys in South Carolina and a friendship that was complicated and real.