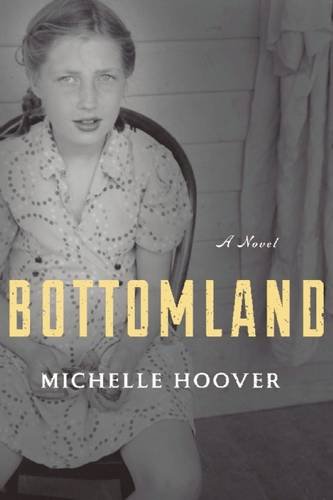

Bottomland

Hess is a German name – and on the bleak Iowa plains in the wake of World War I, that means confronting your neighbors’ anti-German sentiment, being ostracized, banished from their society. It is difficult enough to be an immigrant, struggling to farm and raise your family in this harsh and unforgiving environment – but when you also are not welcome in your own community, the resulting grief and shame are unremitting and the isolation often intolerable.

Esther and Myrle, the two youngest Hess daughters, find a way to leave this bleak existence one night. It isn’t immediately clear why they leave or whether they are, in fact, still alive, but they find a way out of their strangling lives, seeking something better. The family’s efforts to find them are futile; finally the younger son, Lee, who has come home from the war after being wounded, goes to Chicago to find his missing sisters. He returns without them after scouring the boarding houses and waiting at the garment mills at the end of each day – a life almost as bleak and difficult as that they left in Iowa – hoping to spy the young girls and bring them home. But that is not the end of the story, and perhaps it is really just the beginning.

Hoover tells the story of the Hess family in shifting voices from children to father to children. The stark pioneer life vividly portrayed by Hoover is reminiscent of Cather, and her Chicago of Dreiser. Although deeply disturbing and often difficult to read because of the depth of despair experienced by each member of this family, Hoover is an eminently talented writer who captures a reader, moving us forward to a resolution that speaks of hope, reconciliation and acceptance. Highly recommended.