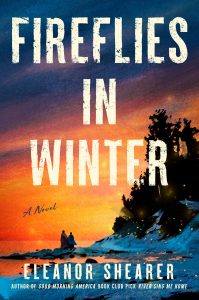

Live, love, resist: Fireflies in Winter by Eleanor Shearer

In 1790s Nova Scotia, a young woman is on trial. Who is she and what is she accused of? From this dramatic opening to Fireflies in Winter (Berkley, February 2026), Eleanor Shearer’s second novel, we slip back a year or two and gradually learn what brings this mystery woman to this precarious moment in her life.

The bulk of the story belongs to Cora, an orphan and a free-born Jamaican maroon, transplanted to Canada. “I’m very proud of my Caribbean heritage,” Shearer explains. “My mum’s parents were born in St. Lucia and Barbados – and I’ve always been drawn to Caribbean history. It was when I was reading about the abolition of slavery in the British Caribbean that I first learned the story of the Trelawney Town Maroons, a Jamaican community made up of descendants of runaway slaves, who were deported to Nova Scotia in 1790.”

When Cora meets Agnes, a young woman who has escaped slavery and now lives alone in the woods near Preston in Halifax county, a relationship begins, and love blossoms. Shearer notes, “Specifically for queer women, because of longstanding cultural prejudices about women’s sexuality (often seen as somehow more passive than men’s), it’s very common that two women in love will be presented as just friends, desexualising their connection with each other. This happens in the present – I remember, growing up, so many examples of female celebrities who were at the time newly sometimes only ambiguously out, like Kristen Stewart or Cara Delevingne, pictured holding hands with their girlfriends with captions describing them as “two close friends”, or “gal pals”.”

Initially, she envisaged Cora and Agnes in a similar vein. “It was only when I started writing the novel I realised my mistake, and that their romantic love needed to be the engine that drove the book.” In her afterword, she talks about the ‘wilful misreading of queer relationships as friendship” – where people look at the past and describe two unmarried women living together as friends and ignoring the possibility that they might be lovers – although this is not something she believes is necessarily done in bad faith. She tells me: “It’s been a core part of my own journey as a bisexual woman! Growing up, often being in all-female environments and developing intense “friendships” with other girls, it’s only looking back that I see some of those as more romantic than platonic.”

So how did she go about developing this queer relationship set more than two centuries in the past? “When writing Fireflies in Winter, set in a time when my characters wouldn’t have access to the language we use to describe sexuality and identity today, I knew I wanted to explore how they, too, would have to learn how to name exactly what it was they felt for each other, and whether it went beyond friendship and into something more.”

She does so with eloquence and in language that is wonderfully evocative, but at the same time, stays true to her characters. She explains, “I’m always interested in the things that can and cannot be said, especially when it comes to writing historical fiction and writing about people who – due to their race, gender, sexuality and class – often leave little archival trace behind. It can be tempting to rush into that gap and over-articulate how these characters might express themselves, so it was a conscious choice to hold back from that and be a bit more realistic with how reticent or quiet these women would have been, given the traumas of what they have each been through by the time that they meet.”

Cora and Agnes have much in common, but they are also from different backgrounds and lived experiences. Shearer adds, “Although Cora may sometimes struggle to express herself, especially as she grasps to understand her place in the world as an orphan, a displaced person and a queer woman, I do think she is the more expressive of the two!”

author photo by Lucinda Douglas Mendies

While the progress of this relationship is at the novel’s centre, many forms of love are explored. Love, the novel tells us is “a small word with so many meanings.” For Shearer, “Love has so many different expressions. One of the reasons for the structure of the book – mostly in close third person, but with brief chapters throughout that take you into the heads of other characters – was to emphasise that each person you encounter in this story also exists in a network of relationships all their own, even if this novel doesn’t explore those in depth. There is Thursday, for example, “the quiet, gentle indentured farm labourer who befriends Cora and helps her in various ways throughout her journey. I wasn’t sure, when introducing him, whether I wanted to play up his potential as a love interest, or even if Cora was not interested in him, whether to make it seem like he was driven by unrequited love. I decided against it, because it’s important to me, as someone with many deep platonic relationships with men, including straight men, to show that such a thing is possible! Without giving too much away, we learn later in the book a little about the source and nature of Thursday’s love for Cora, and coming up with this, too, made me feel closer to him, sharing as I do some of the tragic experiences he’d had to live through.”

Her other major theme is freedom. “It’s a very old philosophical idea,” she says, “the tension between the formal freedom of not being bound by the law and the actual freedom of having the resources to live your life as you see fit. This novel explores that tension. Neither of the protagonists are enslaved when we meet them, but this story is set during a time when slavery was still legal across the Americas – except in Haiti, where revolutionary struggle had already set in motion what would end up being the founding of the first Black republic outside Africa.

“I wanted to show how capricious the boundary between “enslaved” and “free” could be. One minor character, still enslaved, thinks about how the only difference between her and the free Black people in Nova Scotia is that back in the United States during the war of independence, her master was already a British loyalist, while other African Americans who deserted their plantations to fight for the British won their freedom. And we know that in Nova Scotia at the time, even free Black people lived precariously, with examples of people whose papers were stolen then being sold back into slavery. Then, of course, there’s the economic realities of “freedom” for formerly enslaved people – one character in the novel is an indentured labourer, a common arrangement in the province because Black people had no other ways to earn a living and would starve otherwise.

“I hope people come away [from this novel] with a sense of just how complex and varied freedom is, how it means different things to different people, how it requires certain things to actualise, but also how, even under the most extreme of constraints, certain human freedoms – like the freedom to love – remain undimmed.”

The success of Fireflies in Winter is in Shearer’s ability to deliver a satisfyingly dramatic narrative, well-crafted and to shoulder her deep-felt convictions and engage her readers in understanding her character’s experiences. As her story does implicitly, she reminds us: “Even centuries after Cora and Agnes, we still don’t live in an easy time to love. In many places, to be queer or gender nonconforming is to risk death; to be a mother, by blood or by choice, is to risk your child being killed by bombs or starvation or ripped from your arms at a militarised border; and it is so tempting to slip into hate, as a rational response to the ones who do us harm. This is why it still feels urgent to write about love as a form of freedom and of resistance, to remind us why it’s still worth loving, to this day.”

About the contributor: Kate Braithwaite is the author of five novels, including The Scandalous Life of Nancy Randolph (Joffe Books). An editor for the Historical Novels Review, she also publishes SIS-stories, a substack about sister relationships in history and fiction.