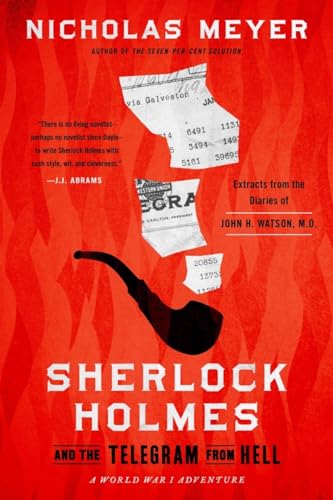

Sherlock Holmes and the Telegram from Hell

Nicholas Meyer received what he’s called the last chunk of Watsoniana: entries from the diaries of Dr. John H. Watson written at the height of World War I when another “blood-soaked” day of treating injured solders ends with a visit from Sherlock Holmes himself sporting a black eye, chipped tooth, and cracked rib.

At the behest of Sir William Melville, director of the recently formed Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), Holmes has been asked to learn how Germany plans to keep the United States out of the war while its U-boats isolate and starve England into capitulation. The adventure takes Watson and Holmes to the American West and Mexico across dangerous seas and bandit-threatened railways to intercept the coded telegram from Berlin that provides the details.

This is the latest in Meyer’s recapitulations of Watson’s works. Like the others, the book reminds Holmes fans how much they enjoy the warm yet often prickly friendship between the sleuth and his chronicler, and Watson’s own words. This time around, however, fiction takes a back seat to fact. The plot recalls the Zimmerman Telegram that was decoded in January, 1917, and the principal figures involved, including Melville and German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman.

Acknowledging that, as Holmes once said, truth is often stranger than fiction, facts can interfere with a good old-fashioned mystery, however. In this case, they dampen some Holmesian characteristics—otherwise unnoticed observations, subtle individual deductions that piece together a complex picture, and machinations of a fiendish arch villain. So, while enjoyable to reenter the Holmesian world, this novel sacrifices the sought-for “elementary” elements for “even if improbable” facts.