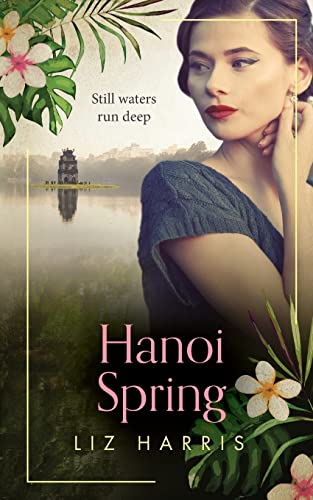

Hanoi Spring (The Colonials)

As Liz Harris’s new novel opens, Lucette Delon, newly arrived in 1930s Hanoi with her husband Philippe, a French colonial bureaucrat in a new posting, is rear-ended in her driveway by the charming Gaston Laroche. Unbeknownst to her, Gaston is a counterintelligence agent with the Sûreté, the security service in the colonial administration. Hanoi Spring then switches to Gaston’s perspective, where we learn he planned the accident as a pretense to enter the Delons’ lives, in order to monitor their next-door neighbor, Marc Bouvier, who is Philippe’s boss. Marc is suspected of aiding the Vietnamese resistance. His colonial-born French wife, Simonne, remains unaware. Gaston’s scheme is successful, allowing him to enter the social lives of the two couples as an amusing fifth wheel. So, for most of the novel, the tone alternates between light chatter and more cynical realism. The Vietnamese resistance is planning something, and Gaston can monitor the moves of those he calls “terrorists.” But more secrets await.

This is the third in Harris’s Colonials series. It is a domestic novel that often reads like a play: the action shifts between the neighboring homes and gardens of the Delons and Bouviers. Gaston’s backstory does take us to the Vendee, a rural French region, around the turn of the 20th century. The focus, however, is Lucette. I wanted more of Marc’s backstory, or even Philippe’s.

After the ending, I am not sure what this novel wants to be: the light, earnest expat friendship story, or the darker story of colonial counterintelligence. I enjoyed each, and either would be great on its own, but as the novel went on, they balanced each other less and less well. The choice of final tone and the overall ending were difficult to believe. I finished the story baffled by one key thing.