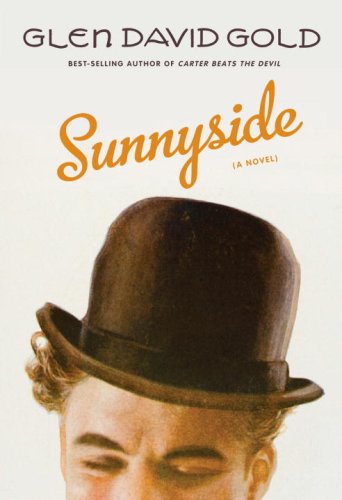

Sunnyside

Gold’s panoramic novel of World War I and early Hollywood opens with a mass delusion: film actor Charlie Chaplin is simultaneously spotted in more than eight hundred places across the U.S. Sunnyside’s main characters, though they never connect, are affected by the incident: Leland Wheeler sees Chaplin drown in a boat off the rugged northern California coast; and Hugo Black witnesses a riot in a small Texas town where the residents are disappointed that Chaplin has snubbed them by not appearing on a train. Chaplin, however, is safely ensconced in southern California — while he is famous, he hasn’t reached the level of celebrity or legend that we associate with him. Gold follows Chaplin, Wheeler, and Black as they navigate difficult personal situations, the war in Europe, and their desire for fame and recognition.

It’s difficult to describe what type of novel Sunnyside is, since it is so many things all at once — a war novel, a romance, a comic novel, biographical fiction, a portrait of a nation on the brink of a new era. The threads of the story connect in unsuspected ways, and readers will find themselves learning things that they did not know about WWI-era film and how it influenced the way Americans (and, through the long arms of cinema, much of the Western world) think about war and celebrity. By delving into stories and legends both well-known and long-forgotten, Gold captures the moment where the modern era of celebrity and American cultural dominance begins — and he does it with style. At the end of Sunnyside, you’ll find yourself awed by the lasting influence of a few seemingly-minor incidents in American cultural history.

– Nanette Donohue

Historical novels usually take themselves rather seriously, even the romantic fantasies. It is rare to find an historical novel which is intentionally humorous. Sunnyside is an exception; indeed it is exceptional in many ways.

Sunnyside is an exuberant, hilarious, anarchic book. It is definitely historical since it is firmly anchored in the years 1916 to 1919 and takes in great historical events such as America’s entry into the Great War, the Western Front and the Allied intervention in the Bolshevik Revolution, as well as the early history of Hollywood and the career of Charlie Chaplin. It is more difficult to decide if this is a novel. There are several different stories told concurrently, all of them fantastical but clearly with elements of historical fact (the author adds the usual appendix which explains which is which, but deliberately leaves large areas in doubt). Each story has its own protagonists and even at the end they do not link up, although they touch each other at points.

Gradually the reader realises that the book is itself like a Charlie Chaplin film, the shooting of which is one of the story lines. We laugh because it touches on things which are too deep for tears, as when Charlie laughs during the funeral of his baby son. The stories are about love and betrayal – all sorts of love including Charlie’s mix of love and shame for his half-mad East End mother and a soldier’s love for the puppy he finds on the battlefield – about death and life, the meaning and the meaninglessness of life and the capriciousness of fate. You will laugh as you read this book and feel like weeping for the pity of all when you reach the end.

– Edward James