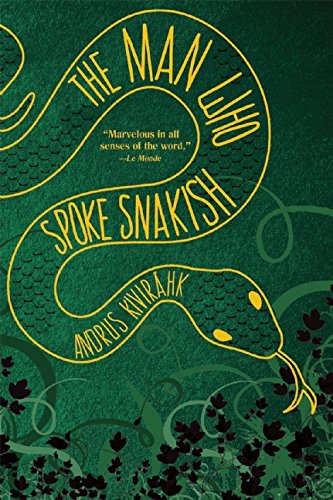

The Man Who Spoke Snakish

In The Man Who Spoke Snakish, Estonian writer Andrus Kivirähk weaves a melancholy, often brutal, tale of the last gasp of an ancient folkloric culture. He describes a people who live entirely in the forest, keep wolves to ride (like horses) and milk (like cows), command wild deer and goats to come to slaughter, and speak the language of their friends the snakes. It is this ability that offers the people dominion over the wolves, deer, and goats, and the forest in general.

Even as the novel opens, though, we find a culture in steep decline. People are leaving the forest in droves, drawn into the tantalizingly modern life of the village with its foreign invaders’ concepts that appear to offer a better life. The title character, Leemet, lives with his widowed mother and sister in their hut in the forest surrounded by an ever-shrinking community. Leemet’s uncle Vootele is the last fluent human speaker of Snakish, and he insists that Leemet learn it equally well. Vootele teaches Leemet about their ancient protector, the Frog of the North, and about Leemet’s grandfather, the last man to have poisonous fangs, which he used to tear into the “iron men” before those invading knights were able to capture him, chop off his legs, and throw him into the sea.

Though there is humor, particularly in some of the early descriptions and observations, the novel becomes ever darker as Leemet finds himself increasingly isolated. Kivirähk can perhaps be forgiven for drawing caricatures on both sides of the culture clash that traps Leemet, since every folktale features archetypes rather than well-drawn characters. Nonetheless, Kivirähk’s tale is poignant in its depiction of the loss of community, of the utter loneliness of living without the people who most understand who we really are.