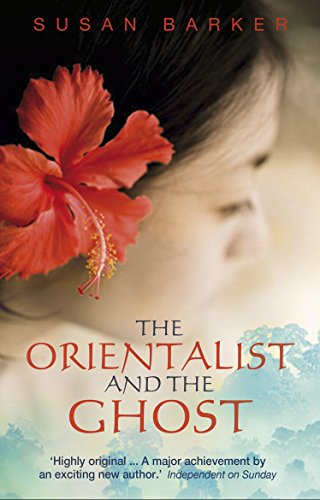

The Orientalist and the Ghost

A more apt title for Barker’s second novel (after the award-winning Sayonara Bar) would be The Orientalist and the Ghosts, as it is the plethora of spirits which command this book.

Christopher Milnar, a classically-trained British scholar of Oriental languages and culture, is sent to Malaya during the Chinese Communist uprising in 1951 to help at one of the many “resettlement camps.” These camps housed thousands of poorly-fed, overworked, undereducated, and often angry Malays of various extractions; the British felt that separating the population from the insurgent threat was the best way to deal with the situation. It’s a steep learning curve for Milnar, as he figures out how to live in a jungle teeming with enemies both human and botanical. Decades later, these enemies still dog his path in their spectral form, from the always-drunk Resettlement Officer Charles Dulwich, to the eviscerated Lieutenant Spencer, to his one and only love, Evangeline, who was a Chinese nurse in the camp. Their relationship was brief and fraught, but out of it was born their daughter Francine, who spent her life—and now, her afterlife—hating her father, who is guardian of her two children.

The book jumps between decades and continents, from the jungles to the cities, the government housing of England to the exclusive boarding schools of Kuala Lumpur. The cast of spirits keeps up, however, contributing background and movement to the narrative, and proving time and again how tenuous the connections are between people who don’t, or won’t, understand each other. Barker is at her best in the jungle and with the crowd scenes, when the distrust and unrest clamor. Whether any of the characters, including the grandchildren, gains enough self-knowledge not to repeat the mistakes of the past is another question.