In the Man’s World of the Past – Jenny Barden in conversation with C. W. Gortner

Jenny Barden

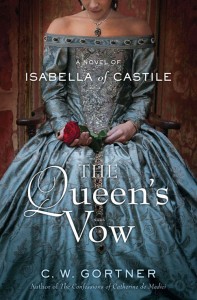

C.W. Gortner is the internationally bestselling author of The Confessions of Catherine de Medici, The Last Queen and The Queen’s Vow, as well as The Tudor Secret, the first in the Elizabeth’s Spymaster series. He is already recognised as one of the finest historical fiction authors of his generation, and he has made a specialty in focusing on some of the most powerful women of the Renaissance.

Jenny Barden‘s debut novel, Mistress of the Sea, is published this week by Ebury Press, Random House. Jenny is programme director and co-ordinator for HNSLondon12, our UK conference this year. She describes herself as an artist-turned-lawyer-turned-writer.

JB: One of the greatest challenges faced by any author of historical fiction must be that of building empathy between readers today, having modern values and mores, and historical characters, whether fictional or real, who would have had a very different way of looking at the world. Where women are concerned, this is bound to be especially difficult since their roles and expectations have changed so much over past centuries. Could you say how you have tackled this conundrum – and has it led to any memorable issues in your writing?

CWG: It always leads to issues. As much as we want to sanitize and empower the past, the stark reality is that for most people, and in particular women, the past isn’t a pleasant place. The world was often dark, cruel: there were no civil rights. It’s therefore a challenge to depict these women in ways that modern readers can identify and empathize with, simply because we see the world in such different terms. We reflect our notions onto the past, which explains why we are so endlessly fascinated by ladies like Anne Boleyn, whom we perceive as bucking the system. Yet we also know that even a queen could find herself prey to the male-dominated society in which she lived: this is not a flaw of her character, but rather an unfortunate reflection of her era. What I try to do is find the similarities with our experiences.

JB: As an author you’ve concentrated on some of the most notable women who played a role in the history of the Renaissance era, yet we generally think of noble women at this time as being very constrained, usually married off young by their fathers, their primary function being to beget male heirs. How have you managed to invest your heroines with enough freedom of action to make them interesting to readers now?

CWG: They themselves have invested it; they display it within their lives. It’s just a matter of looking deep enough to find it. Women were constrained, both at the top of the pecking order and at the bottom: that is the reality. However, the women I’ve chosen to write about still show strength of purpose and character. I don’t think of them as ‘heroines’ because that term evokes, for me, high expectations: these women are not Xena, Warrior Princess. They struggle with the confines of their gender and particular circumstances; it’s their struggle; that fight against the tether, though they may not succeed, which fascinates me. I am always drawn to the subtleties of life, to how we navigate the seemingly anarchic circumstances we are handed, often through no fault of our own. For example, Catherine de Medici was married

JB: Women are being given particular prominence in historical fiction at the moment, perhaps because in times gone by they have been rather neglected by historians, but you seem to be going even further than filling in the gaps – you have taken women who have been demonised or maligned and shown them in a new light. Catherine de Medici, traditionally viewed as the evil murderess behind the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, is portrayed sympathetically in your novel about her, and the behaviour of Juana ‘the Mad’ becomes understandable in The Last Queen. Has there been a deliberate attempt at rehabilitating these women on your part? – or are these characters who fascinate you, who have become more real, and ‘human’, as you have brought them back to life in your fiction?

JB: The minutiae of daily routine must have filled much of the time available to the women you write about: dressing, eating, grooming and praying. Plainly your research has been meticulous, but were there any surprises you came across – details about habits and customs that perhaps you felt loath to include because they would appear too alien to readers today?

CWG: Yes, to a certain extent. I found details that I was overjoyed to discover; for example, Catherine de Medici refurbished a crumbling menagerie in Amboise so the lions would be better housed. Isabel of Castile decided to learn Latin after she became queen and championed women’s education. Juana stood up to the king of France when no one else dared. And then, there are the aspects of the characters which we’d find tough to condone and I was indeed loath to include, though I did anyway, such as Catherine’s lack of public remorse or Isabella’s decision to authorize the Spanish Inquisition. I don’t try to make the unpalatable less so; I do try to elucidate it. That said, there are certain details of life in the past which I don’t dwell on incessantly. While I strive to convey an authentic sense of the era, we can only take so many mentions of the lack of sanitation and rampant cruelty. We don’t want to hear how dirty everything was over and over; few of us want to be reminded on a regular basis that those gorgeous gowns sweeping the floors could not be dry cleaned or that lice infestations were endemic or that animals died by the hundreds in baiting pits, their bloody ends often enjoyed by those very queens we admire.

JB: We’ve come to think of the great women of Renaissance times as ruling through men since the organs of sovereignty were then so male-dominated (the church and judiciary, administration and the military), yet is this too simplistic a view? Do you think women had more authority than has generally been credited, perhaps through sexual manipulation, perhaps through other means?

CWG: Oh, absolutely. In Castile, as in England, a woman could inherit the throne as sole sovereign. Isabella wore her crown in her own right: she didn’t rule through male authority any more than Elizabeth I did. Juana’s tragedy was, arguably, the fact that she held more power than her husband by legal mandate. Women indeed had more influence and authority than history tends to credit, and they played crucial roles in the shaping of their countries. Was there sexual manipulation? How could there not be? Women have always used the weapons at their disposal: sex is one of those. But they also used acumen, intelligence, compromise, and ruthlessness as much as their male counterparts. I find it a fallacy to see the past in black-and-white terms.

JB: What’s your favourite instance from the past that gives an insight into the true relationship between women and men in the sixteenth century?

CWG: Isabella of Castile’s coronation: her husband Fernando was away when she unexpectedly became queen. There was danger all around her; she had to seize the moment. She had no time to send a message to Fernando and await his reply. When he arrived in Castile, you can imagine his reaction. And he let everyone know it, especially Isabella. What did she do? She set herself to creating the illusion of equality. This is the true relationship: she’s doesn’t submit because he throws a tantrum. She rolls up her sleeves and goes to work.

CWG: I think the balance of power was, to a certain extent, influenced by the particular country’s circumstances and history; but overall, few sovereign queens had been successful before the Renaissance and even fewer men believed a woman could rule. That said, I think England had a unique period in that within a relatively brief span of time, we experience a dizzying six queens for one king; then, after a brief kingship, we see one of England’s first sovereign queens mount the throne as Mary I, her tumultuous and tragic reign followed by Elizabeth’s. I would imagine that for those who lived through these events – and the longer-lived got to see most of it – the balance of power must have appeared skewered, even at times to be crumbling. I believe that after everything that came before her, the nation was primed for Elizabeth. It’s the main reason I set my Spymaster series within this particular crevice in time, just before she comes to the throne, as England is convulsed by the after-effects of the break with Rome, the death of Henry VIII, the fractious reign of Edward VI, and disappointment of Mary I. Elizabeth is fascinating because she arrives on the scene just when we need her the most; and she proceeds to play the game of power, both politically and between the sexes, with a startling ingenuity. I always smile when I come across a mention of that old legend that she was secretly a man, because she cultivated both the masculine and feminine in equal parts. That legend is an illusion which she herself set out to create. She would have laughed at the legend, I’m sure: laughed and loved it.

JB: This leads me onto one last question: Will you ever write a novel about the life of the Virgin Queen?

CWG: Oh, of course! She’s an incredible woman, an icon; yet also extremely fallible and prey to neurosis, the best and worst of both her parents. She’s an historical fiction writer’s dream. But, she’s also been covered quite a bit and I’d have to feel as if I had something fresh to bring to her story. I think for now, my Spymaster series gives me that. If all goes well, I’d love to continue to write about Brendan’s work as a spy on Elizabeth’s behalf. Her reign was long. There is so much opportunity to explore through their fictional relationship. He is my witness to history; thus, he can experience his life through hers, in ways that provide that unique angle I always seek.

JB: Thank you so much for agreeing to be spotlighted in this way, and for giving such fascinating and enlightening answers.

CWG: So lovely to be here; it’s my pleasure. Now, if I may be so bold, I’ve had the wonderful opportunity to read and endorse your upcoming novel Mistress of the Sea. I enjoyed it so much, in particular the unique story it portrays. Could you please tell us a little about the book? Also, what drew you to this particular place in time and what do you think it says about the role of women in our male-dominated past?

Very high and powerful lady:

Several women came to this province of Río de la Plata along with its first governor don Pedro de Mendoza, and it was my fortune to be one of them. On reaching the port of Buenos Aires, our expedition contained 1,500 men, but food was scarce, and the hunger was such that within three months 1,000 of them died… The men became so weak that all the tasks fell on the poor women, washing the clothes as well as nursing the men, preparing them the little food there was, keeping them clean, standing guard, patrolling the fires, loading the crossbows when the Indians came sometimes to do battle, even firing the cannon and arousing the soldiers who were capable of fighting, shouting the alarm through the camp, acting as sergeants and putting the soldiers in order, because at that time, as we women can make do with little nourishment, we had not fallen into such weakness as the men….’

I often think that women did much more at this time than the history books would have us believe!