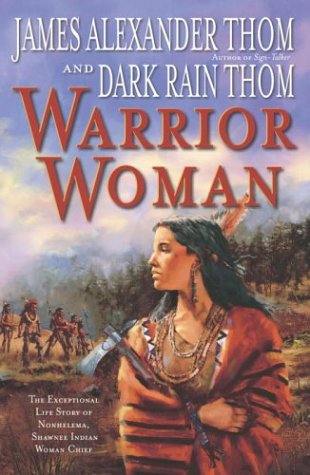

Warrior Woman

The story of Nonhelema needs to be told. A Shawnee whose name means “Not a Man,” she lived during the Revolutionary War and years of U.S. expansion while “heroes” like Daniel Boone drove her people from Virginia and Kentucky. Literate, multilingual, tall and beautiful, she bore children to two white lovers—and lost the acceptance of her people through her attempts as diplomat.

Unfortunately, somewhere between a fine opening where the native women’s council is consulted before their men can go to war, and an ending with some power, if a bit preachy, this version bogs down hopelessly. Too many characters too ill drawn who simply “appear,” and masses of emotionally disjointed events reported from a distance, are major slowing points. In particular, Nonhelema’s conversion to Christianity and continuous attraction to it I found completely unbelievable, and it is the novelists’ job to make even such choices in their heroes sympathetic. I longed for a nonfiction history of the events in hopes that I might find there the comprehension this novel failed to provide. Also, “Warrior Woman” is a misleading title for an epic about a woman whose goal—to the point of stupidity, it seemed—was to spread peace.

On the other hand, there are some truly beautiful and rich descriptions of Native life, although the spiritual underpinnings seemed spotty. Tecumseh makes a youthful appearance along with his brother, the Shawnee Prophet. And the scene where the noble old chief Moluntha stands waving his American flag while white soldiers come through his peace village “like the teeth of a comb” is heartrending. Desperately he holds the treaty, “putting his finger on the place where he signed it, showing the officers his mark” while his people die.