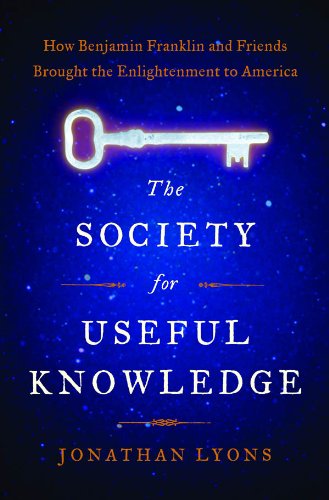

The Society for Useful Knowledge

On the cusp of the American Revolution, a group of humble craftsmen came together to successfully challenge the central tenets of European scholarship. These “leather apron” workers – led by such figures as Benjamin Franklin, David Rittenhouse, and Benjamin Rush – believed that the practical sciences must take precedence over the humanities so long hailed as hallmarks of a classical education. Only citizens who cultivated “useful knowledge” could win the War for Independence – and lead productive lives in the new country they would create.

Jonathan Lyons chronicles this fascinating period – a time when natural philosophers toured the colonies giving public demonstrations of electricity, when astronomers synchronized their clocks in preparation for the transit of Venus, when vehement editorials debated the question of whether installing lightning rods defied the hand of God. Torn between history, biography, and manifesto, the book sometimes loses forward motion, and sometimes skips around distractingly. And Lyons takes little time to consider the potential negative consequences of the production and exploitation this scientific revolution set in motion. Overall, however, I was caught up in the intricate world of telescopes, clocks, and chronometers – and the ticking gears of scientific endeavor that often go unnoticed behind the scenes of history.