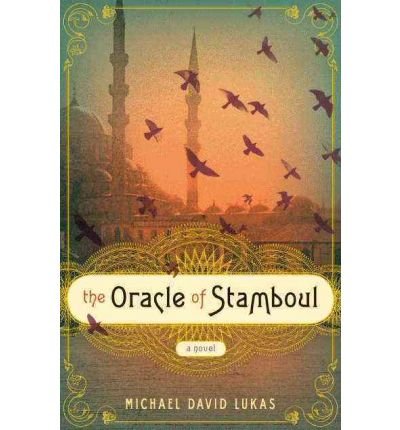

The Oracle of Stamboul

In the late 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was a husk of the power that had shaken the Mediterranean world. The last autocratic Sultan, Abdul Hamid II, reigned over a society hopelessly corrupt and divided, surrounded by avaricious modern states. Michael David Lukas’s much trumpeted novel The Oracle of Stamboul is set in this period, exercising the conceit that the Sultan at some point fell under the influence of an eight-year-old girl.

The girl, Eleanora Cohen, is a savant, brilliant from the cradle, and having no resemblance to a real child; she serves to see the details of a gorgeous display. Beginning in Constanta, where she is born (accompanied by a faithful flock of purple hoopoes), she provides a placid description of provincial life in the Empire; then she whisks herself off to Stamboul, where almost effortlessly she reaches the palace.

“Through an open doorway, she could see a vast courtyard peopled with beautiful young women, plucking at string instruments and murmuring to each other in quiet, giggling tones. Here was the fountain flowing, there the carpets spread out and cushions set in a row.”

Not too much else happens. The details of life, the suffocating weight of history, are lovingly and exquisitely written, but it seems at a distance. There’s no engagement, no excitement, we all know how this ends, and Lukas doesn’t really make us care.