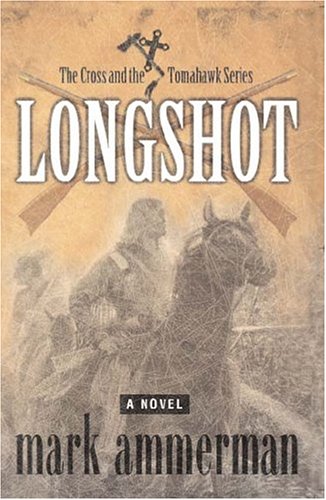

Longshot

The first person narrative begins in 1750 Rhode Island, where Christopher Long and his Narragansett friend Caleb clear out the tribe’s ancient council rocks. Called “Longshot” for his marksmanship, Long tries to convert his friend to the Church of England, but Caleb has his own gods. Caleb lets Christopher ride his black horse, a lyrical passage of blue skies and salt air. Their friendly debate heats up as the topic turns to the land where the Indian village stood, now owned by a planter. Caleb’s mother works in his household.

They stop by Hazard’s farm and Chris explains his plan to go to Ohio to Joy, Caleb’s mother, who is worried her son will exact vengeance on the man responsible for his father’s death. The question of Joy’s faith is handled in a way that leaves no doubt, Christianity is the only true religion. Chris can be forgiven his parochial attitude, but the Reader’s Guide states baldly that Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam and earth worship are all false religions.

The texture of the writing lets us experience Narragansett Indian life and traditions. The personality of Caleb resonates, and when Chris tries to convert him, it’s a nice conflict. The friends’ grand adventure along the Ohio River is sidetracked by Caleb’s blood lust. Chris goes on ahead, with lush descriptions of autumn in upstate New York, and characters like Conestoga Joe, an old Susquehannock, whose way of speech is highly individualistic. The theme is revenge, whether by fair fight or stealth, that he who lives by the tomahawk…

Longshot’s survey of the land turns into a census of remaining Eastern Indians. Basing his novel on given facts, the author does a good job of coloring in. Extensive bibliography, notes and glossary complete the experience.