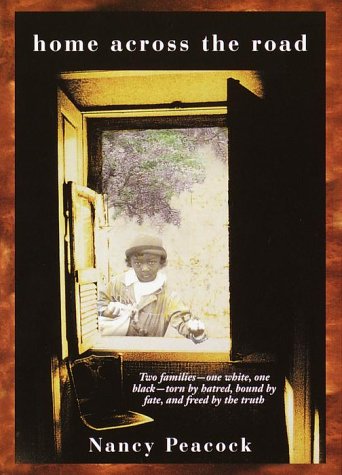

Home Across the Road

Generations of the Redd family, divided into the white Redds and the black Redds, people this novel which the New York Times Book Review called “a palimpsest.” China, the character from whose point of view the story unfolds, spans the years when events took place and keeps alive the family history. When she sees an object such as abalone earrings, layers of meaning turn that object into a trope. The symbol opens up to a story that resonates through each generation.

Those earrings belonged to Lula Anne Redd, whose son showed them to Cleavis, drawing her attention to the boy’s resemblance to her husband Jennis, who had been sleeping with the slave Cally. Lula Anne sold Cleavis away at age six, and then Cally stole the earrings as a memento and a small revenge.

The cotton plantation in North Carolina, its crumbling mansion, and the house across the road built by the descendants of slaves, are all powerfully evoked. Roseberry, the big house, claimed China’s life work from the time she was 14.

By choosing this protagonist, the author sets herself a difficult task. China is not someone who goes out and resolves her problems. She waited on the white Redds and now that the last scion of the family is gone, she waits to die. Within the limitations of her life, she maintains an enviably simple existence. Among her few possessions are the shell earrings, which she believes curse the white folks and keep her own babies safe.

As Peacock revisits this territory over the years, adding layer after layer to the symbols, the repetition lends a mythic quality to the story. The problem with this is predictability: the outcome is preordained. The story has a strong rhythm, and characters who evoke emotions that have nowhere to go. I came away with an appreciation for the deep, deep game and long-term determination of the oppressed.