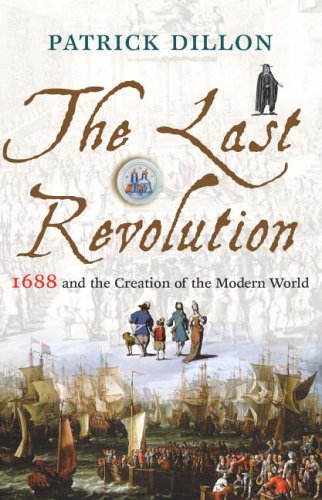

The Last Revolution: 1688 and the Creation of the Modern World

The Revolution of 1688 has been called ‘bloodless’. On the whole the description holds. But as Patrick Dillon’s fascinating book makes clear, ‘bloodless’ should not be taken to imply anaemic. For according to Dillon its consequences were more profound and far-reaching than is commonly supposed and the myth of the Glorious Revolution contains within it much more than a grain of truth. For one thing the absolute power of kings had been broken. It was this and what he saw as the toleration and openness of 18th-century English society – in marked contrast to pre-revolutionary France – which won the admiration of Voltaire.

It was not yet democracy, but the necessary conditions for the development of modern liberal democracy – toleration, freedom of the press, freedom under the law – were surely in place. This is the burden of Dillon’s argument, and I agree with him. Britain was certainly the freest country in Europe at the time, as Voltaire recognised. For anyone interested in British history, this is an immensely important book. And the moral for historical novelists? Think twice before romanticising those counter-revolutionaries, the Jacobites.