Mid-Air: Two Novellas

To Henry James, the novella—longer than a short story, shorter than a novel—was “the beautiful and blessed nouvelle.” And in Mid-Air Victoria Shorr beautifully demonstrates its high potential.

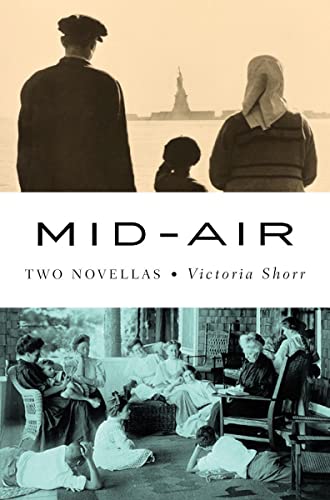

At first “Great-Uncle Edward” and “Cleveland Auto Wrecking” seemingly share nothing but the limpid prose in which they’re told. Yet together they form a deeply satisfactory whole that evokes the up-and-down history of America itself. “We must have passed at one point in mid-air,” reads the book’s epigraph; “them on the way up, us free-falling.” Next come two novellas that contrast and parallel.

Set in the 1970s, “Great-Uncle Edward” traces the decline of an aristocratic old New York clan, as seen through the eyes of an outsider newly married into the family. Each character, from the ancestress who met George Washington to the 20th-century aunt who resembles a Bowery bum, carries a resonating story.

“Cleveland Auto Wrecking” traces the rise of a very different family. The founding father arrives at Ellis Island as an illiterate twelve-year-old. He never learns to read. But he “sees” numbers, especially money, as “bundles of barley,” and he discovers the value of junk. Slowly “the good junkman” scrabbles his way into prosperity by “weaving gold from nettles.”

So does Shorr, dipping skillfully into the consciousness of her many characters as they move from the early to the late 20th century. Her choice of period details is invariably brilliant: haircuts, clothes, cars, TV shows, and menus are perfectly synchronized with the changing times. And although the times change, they also connect. Uncle Edward knew an old lady who knew the old lady who spoke to Washington as a girl. He tells “family tales,” she writes, that “shed light well beyond the circle they depict.”

Yes! And so does Victoria Shorr.