Where to Draw the Line? Fantasy Novels with Historical Settings

by Ann Chamberlin

Some of the most rancorous exchanges I’ve had online concern where we draw the line of fantasy in novels with historical settings. I have been told that Christian miracles make the grade because “the life of Christ is proven fact,” but having Greek or Roman gods put in an appearance or answer prayers is fantasy because “we have proven them wrong.”

Some of the most rancorous exchanges I’ve had online concern where we draw the line of fantasy in novels with historical settings. I have been told that Christian miracles make the grade because “the life of Christ is proven fact,” but having Greek or Roman gods put in an appearance or answer prayers is fantasy because “we have proven them wrong.”

To declare such a doctrine is to write out of the canon Mary Renault, whom I consider my greatest inspiration. I love how young Alexander sees the god, whose son he believes he is, leaving his mother’s bedchamber in Fire from Heaven (1969). The sight defines Alexander’s relationship to Philip of Macedon, his “real” father. It defines the course of Alexander’s life, and to me is a much more valid explanation than that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob had a hand in this. It beats the heck out of such pious offerings as The Robe (1953) or Ben-Hur (1959) in terms of historical verisimilitude.

Some hold that such visions are okay as long as the reader can see that there was some “real” scientific explanation: Olympias had a lover of impressive stature. Others believe that without using a high democratic, capitalist, or scientific mindset to solve every dilemma and running circles around the ignorant barbarians among whom he is forced to live, the hero cannot be a real hero after all. Often, to my mind, such heroes become very like Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), and I do call them fantastical.

For me, personally, entering a very different mindset is part of the main reason I read and write historical fiction. An inspirational historical that gives very American evangelical ideas to any time period before Joseph Smith and upstate-New York’s Burned-Over District — and I’ve read some from pre-Christian eras — is pretty much fantasy in my book and does not satisfy.

Time and again, my novels get labeled “fantasy,” sometimes, as in my most recent offering — a trilogy entitled The Valkyrie, with the first volume entitled The Choosers of the Slain (Penumbra, 2014) — with no “historical” attached. And yet, I researched the dickens out of my subject. When my heroine Brynhilda — yes, that Brynhilda — first sees Odin’s steed Sleipner, she sees the eight-legged creature of myth. That the horse presently divides himself in two so there is a mount for her to ride and join the god in his travels is mere divine sleight of hand. I could not neglect the quote I use at the start of volume one from the twelfth-century historian Saxo Grammaticus, when he says that women who gave up the usual female pursuits of hearth and home to become Valkyrie did actually exist. Saxo also provided the quote that will head volume three, indicating that Odin was a man who went around the world fooling people into thinking he was a god; Saxo, of course, was a Christian. I do not ignore the archaeology (my major, actually) that tests the DNA of several buried Vikings and discovers no Y-chromosome.

My Joan of Arc Tapestries series (St. Martin’s Press) — where Joan is burned as a witch because she was one — gets labeled fantasy (even heresy by true believers) although I mean to recreate a world in fiction as Carlo Ginzburg’s The Night Battles (Routledge, 1983) and Margaret Murray’s The God of the Witches (Sampson Lowe, 1933) do in non-fiction. On the other hand, nobody’s thought to do the same to my trilogy about early Islam, where the jinn are present and miracles are performed. Jinn are in the Quran; to not believe in them could be considered un-Islamic, and to not believe in witches (which according to the Old Testament shall not be allowed to live) is to be neither Jew nor Christian, I suppose. Does The Sword and the Well escape from the nomenclature “fantasy” because I self-published these titles and had control of genre identification? Or is it because some readers have a very low opinion of Islam and think its believers must be deluded anyway?

How else is a novelist to deal with historical figures who hear voices, see visions? Our bizarre society likes to consign them to regimens of pills or the sanatorium. Off their meds, these folks shoot up our schools and our cinemas, so they say. I don’t think we have the best grasp of such aspects of the human mind. New historical fantasy titles such as the ones I’ve reviewed below can open so many doors to exploration.

We have that chimera, steampunk, the popularity of which no one who sits in the vantage point of my bookstore at the Arizona Renaissance Festival can deny. Yet Mark Hodder’s The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack (Pyr, 2010), the best of the subgenre I’ve read, is the book I have to credit with my knowledge of the true-life attempt on the young Queen Victoria’s life in 1840. And what better way to explain that bane of London bobbies on night shift, the Victorian “myth” of Spring-Heeled Jack, than with a good dose of steampunk gears and widgets? I have to delight in the older Majesty on steam life-support, even though I know it’s not “true.”

If you have any interest in turn-of-the-nineteenth-to-twentieth-century immigration to New York City from all over the world, you might start with Helene Wecker’s The Golem and the Jinni (Harper/Blue Door, 2014) where, as the title suggests, the supernatural creatures enter the cultural melting pot as well. The images of streets of Yiddish and homeless newcomers will compare favorably to any other historical novel you may have read, with the added melding of Maronite Christian Arab with Ukrainian Jewish paranormal threats, which can also serve as metaphors for those of us taught to be obedient and ignore our own wishes. Some of the material for this book must come from the experiences of the author’s own family; how more real can you get?

Also based on Jewish tradition but of a much more ancient time comes Maggie Anton’s Enchantress (Plume, 2014), the second of her novels of Rav Hisda’s daughter in the fourth Christian century, at the time of the formation of the Talmud and the struggles of the rabbis to patch together what was salvageable of their faith and practice after the fall of the temple of Jerusalem. What few in recent, more “rational” times accept is just how full of magic and spells the Talmud is, which was perfectly understandable for the time and place. Our heroine consults Chaldeans, others create what must be the precursors of golems and sides of beef for the Sabbath meal.

Anton has written a number of blogs discussing her use of the supernatural and shared her thoughts with me for this article. “In 4th-century Babylonia where ‘magic’ was real,” she writes, “everyone believed that illness was caused by demons or the Evil Eye, and cured/prevented by amulets and incantation bowls. My heroine is one of these healers, her methods would be considered magic today. Yet, all the spells I include are authentic, that is from archaeological evidence and ancient magic manuals. So is my novel a historical fantasy or not? One person’s miracle is another person’s magic.” (http://readingthepast.blogspot.com)

Anton’s more sober attempt to bring ancient spells into reality is in some ways less successful at creating a world the reader gets sucked into than her polar opposite, A Plunder of Souls by D. B. Jackson (Tor, 2014), third in a series. This novel is set in the midst of a historical smallpox epidemic in 1769, in a Boston occupied by British redcoats and struggling under trade embargoes. The true focus of the tale, however, is a plot to rob the graves of the newly dead from the well-known cemeteries where those involved in the Salem witch trials are buried. Against this backdrop plays out a plot that reads like ignis ex cruore evocatum, the high fantasy/LARP (Live action role-play) trope of a battle of the conjurors and who has the most cards up his sleeves. And yet the author has a history degree.

Elisha Barber by E. C. Ambrose (DAW, 2014) evokes London, Jewish men of medicine, and the fourteenth-century arrival of gunpowder weapons to forever alter warfare, but the names of battles, kings, and princes are none that history books recite. Nothing could be more real than the descriptions of barbering performed by the title character — the sort of barbering that saves lives torn apart on the battlefield and which conflicts with butchering surgeons and Salerno-trained physicians inclined to experiment on fallen cannon fodder. The reality of description bleeds seamlessly over into the magic of magi so that all are vividly believable. I haven’t enjoyed such visceral descriptions of the physical trappings of the late Middle Ages in any “straight historical” in years.

Li Lan, the heroine of Yangsze Choo’s The Ghost Bride (Morrow/Hot Key, 2013), gives us a tour of the Chinese afterlife as she is faced with the prospect of marrying the dead scion of a wealthy family to repair the fortunes of her own clan. I cannot imagine a better way to capture this practice, which is especially popular among émigré Chinese in Malaya, as here and elsewhere, than to have a sympathetic character do battle with the otherworldly manifestations of the paper-doll servants’ dutiful descendants, who burn to serve their dearly departed. Pursuing this quest, Li Lan solves the mystery of who murdered her unsavory suitor and forges a brave new life for herself.

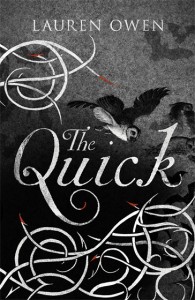

Lauren Owen bridges the gap between historical and horror in The Quick (Random House, 2013). The gentlemen’s clubs of Victorian England and Oscar Wilde with his mauve gloves wrangle with creatures polite society will not name. Vivid details fill the pages, from toasting forks and how to properly lay the parlor fire, priest holes and wonderful leather-lined libraries, to blood-hungry street urchins and the efficacy of holy water against the undead.

I hope you’ll take your pick from the eight titles I’ve shared here — including, humbly submitted, my own — for a sense of the spectrum of possibilities that open up once the so-called fantastic is added to the historical.

About the contributor: Ann Chamberlin is currently chair of the HNS North American conference. She has published twenty books including international bestselling historical novels, and her historical plays have been produced from Seattle to NYC.

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 72, May 2015