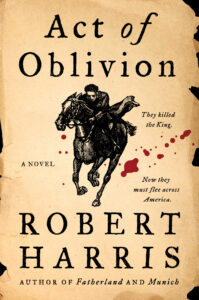

The Hunter & the Hunted: Robert Harris’s Act of Oblivion

WRITTEN BY GORDON O’SULLIVAN

In his latest novel, author Robert Harris “set out to create an epic.” He soon found himself on a marathon journey, admitting that Act of Oblivion (Hutchinson Heinemann UK/Harper US, 2022) was “the hardest of all my fifteen novels to write.” Where did this narrative trek begin? Harris’s attention was initially caught by “a reference somewhere to ‘the greatest manhunt of the 17th century’”, he says. “I read about the hunt in 1660 for the men who had signed the death warrant of King Charles I or had sat as judges at his trial.” That hunt began almost immediately after the restoration of the executed king’s son, Charles II. An Act of Free and Generall Pardon Indempnity and Oblivion pardoned all past treason against the Crown but specifically excluded those involved in the trial and execution of his father. These ‘regicides’ knew that all they could expect of the new king was the agony of a traitor’s death, and most quickly fled into exile. When Charles II offered a substantial reward for their capture dead or alive, the regicides all became hunted men.

In his latest novel, author Robert Harris “set out to create an epic.” He soon found himself on a marathon journey, admitting that Act of Oblivion (Hutchinson Heinemann UK/Harper US, 2022) was “the hardest of all my fifteen novels to write.” Where did this narrative trek begin? Harris’s attention was initially caught by “a reference somewhere to ‘the greatest manhunt of the 17th century’”, he says. “I read about the hunt in 1660 for the men who had signed the death warrant of King Charles I or had sat as judges at his trial.” That hunt began almost immediately after the restoration of the executed king’s son, Charles II. An Act of Free and Generall Pardon Indempnity and Oblivion pardoned all past treason against the Crown but specifically excluded those involved in the trial and execution of his father. These ‘regicides’ knew that all they could expect of the new king was the agony of a traitor’s death, and most quickly fled into exile. When Charles II offered a substantial reward for their capture dead or alive, the regicides all became hunted men.

Having decided that his subject would be a fugitive hunt, Harris thought “it would be interesting to create the character of the chief manhunter.” While most characters in Act of Oblivion are based on historical figures, Richard Nayler is fictional and styled by the author as the secretary of the regicide committee of the Privy Council. Harris now had his ‘chief manhunter’, but which fugitive regicide would he select for his novel? “I had to choose which of the men he was hunting I should focus on. That led me naturally to the real-life historical figures of Edward Whalley and William Goffe, a father-in-law and son-in-law.” Colonels Whalley and Goffe were high-ranking Cromwellian soldiers who had signed the king’s death warrant. Whalley was also Oliver Cromwell’s cousin. In the novel, Nayler quickly becomes obsessed with bringing these two men to royal justice, and an unrelenting chase begins.

The 17th century hasn’t been the most popular setting for historical novels, so what attracted Robert Harris to this period? “I was drawn principally to the landscape of America in its earliest days – what it would be like to be on the run across this vast, dangerous landscape, fleeing from one tiny, isolated Puritan settlement to another.” As Act of Oblivion’s tale travels back and forth across the Atlantic, Harris had to “recreate London in the 1660s, from where the manhunt was run.” That enabled him “to write about the aftermath of the English Civil War and the declaration of a republic – a seismic event that affected not only my country but the whole world.” He also uses flashbacks and the clever device of Whalley writing a memoir, as many English Civil War leaders did, to further explore the political differences that led to fighting on the battlefield. Whalley, for example, as both gaoler to Charles I and comrade of Oliver Cromwell, is ideally placed to provide the reader with insight into both the personal characters and the political personas of these key Civil War figures. The political ideas that the English Civil War provoked would eventually make their way to the English colonies. Harris “found it fascinating to discover the extent to which the revolution that failed in England transferred to America and eventually succeeded there.”

Robert Harris has created a fully immersive world in Act of Oblivion, and he had to work long and hard to achieve it. “I researched pretty solidly for eight or nine months, from the autumn of 2020 to the early summer of 2021 – mostly during the COVID lockdown in England. I immersed myself in detail seven days a week – there was little else to do!” That sense of being ‘locked in’ is fully represented in the novel with the two regicides hiding away from the world during the day, venturing out only at night, forced to avoid the danger of contact with other people. The research was only the start of Harris’s longer-than-usual writing journey, though. “Then I started the actual writing, and it took me about a year – twice as long as I usually take to complete a novel.” No wonder Harris feels that it was the hardest of all his fifteen novels to finish.

From the very beginning of Act of Oblivion, there is a cinematic feel to the novel with hints of films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid: clear markers of an epic chase about to start. Harris did in fact “think about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. I had them call themselves Ned and Will (which I think it’s likely they would have done).” In addition, there used to be a TV show when I was growing up called Alias Smith and Jones, and Ned and Will also had to live under false names.” But it isn’t just the characters in Act of Oblivion that evoke classic movies or television series; it’s also the movie-like panorama of American expanse, familiar to fans of Westerns but so alien to Whalley and Goffe, that the author creates. “The landscape they have to travel across – trekking in midwinter from Cambridge, Massachusetts to the Connecticut River, for example – is obviously very filmic.” Although the two regicides are initially feted by the many fellow Puritans living in America at that time, their welcome quickly fades as the royal pressure for their surrender intensifies. In constant fear of betrayal and arrest, Whalley and Goffe are forced to move constantly, in classic chase movie style. As Harris says, “the sympathy of the reader, or audience, is naturally awakened by people on the run who face a dreadful death if they are caught. That tension is the stuff of adventure stories, and films.” Robert Harris is a past master at piecing a narrative puzzle together, and his new novel is no exception. In Act of Oblivion, his characters don’t just plug gaps but also deepen the context and complexity of the story. This is a chase novel, but the complex characters ensure that the reader stays the course. Harris underlines that “it was conceived both as a chase novel and a character study.”

The author didn’t make it easy on himself with the characters that he chose to pursue, “one of the hardest tasks was to humanize my fugitives – these two, stern, highly religious, revolutionary Puritan colonels.” The period of the English Civil War and its aftermath isn’t easy for the modern reader to navigate. The deep and sincerely held religious beliefs that permeate the 17th century, particularly on the Puritan side, can seem almost alien in the 21st century. The two regicides, for example, believed firmly that they were part of the elect, the chosen few who would avoid damnation, while Goffe was convinced that the world was set to end in the year 1666. Harris doesn’t try to explain the intricacies of 17th-century Christian doctrine in depth, however. Instead, he offers the reader only as much information as absolutely required to understand his characters. As the harsh toll of months and years in hiding increases their personal, political, and religious doubts, he allows his characters the space to do their own soul-searching. Goffe is forced to come to terms with the apocalypse failing to arrive. Whalley, through his memoir, begins to question his former political certainties, even re-interrogating his relationships with both Cromwell and Charles I. The use of other characters such as Frances, Whalley’s daughter and Goffe’s wife, add further complexity to the novel without complicating the plot. Their implacable foe, Richard Nayler, is no simple hero or villain either. His personal motives for pursuing the fugitives can be empathised with even though he is just as fanatical in his political beliefs as the most fervent Puritans in their religious faith. In previous novels like those in the Cicero Trilogy (2006, 2009, 2015) and An Officer and a Spy (2013), the author created morally ambiguous characters. In Act of Oblivion, he’s also managed to pull off that difficult balancing act as the novel moves back and forth between the hunter and the hunted. The reader can care about what happens to the main characters while also being repelled at times by both their attitudes and their actions.

Having written so many historical novels, what still challenges Harris about writing about the past? “I think there are multiple benefits in writing about the past, so long as you bear in mind the old adage, ‘just because it’s true doesn’t mean it’s interesting’. You have to guard against putting in details that aren’t relevant to the story simply because you know them.” As a writer, when you have learned to do that, you can “immerse the reader in an unfamiliar world. You have the excitement of describing something that actually happened. And you can use the past as a mirror to examine the present.” Although Harris warns that “you should guard against straining for effect by making comparisons that don’t really apply.”

Robert Harris has only one rule that he follows when writing historical fiction, “never to put something in a novel that I know for sure didn’t happen.” He recommends sticking to “a framework of the facts, and then feel free to invent around them.” The fugitive hunt for Colonels Whalley and Goffe is a perfect example of putting this into practice. “We know enough to follow where they went and who they met, and not enough to know how they managed to survive so long, often living in the wild, or hiding in cellars, barns and attics.” In Act of Oblivion, Harris has invented freely and fruitfully around his research to create a deeply satisfying chase novel and character study.

About the Contributor: Gordon O’Sullivan is a freelance writer and researcher.

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 102 (November 2022)