The Artist’s Call, the Writer’s Calling

by Stephanie Renée dos Santos

Art is a global language. It has the power to communicate, connect, engage, transform, relate, and heal. Artistic processes, purposes, and pieces have been the interest of writers since the time of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (circa 77-79 AD), which featured passages on the development of Greek sculpture and painting. One can trace from these pages the ideas of the Grecian sculptor Xenokrates of Sicyon (circa 280 BC), possibly the first to write about the arts. In China there are references to ancient painting practices in The Record of the Classification of Old Painters (circa 550 AD), attributed to later influencing the sixth-century writings of Six Principles of Painting by Xie He.

In early fifteenth-century Italy, Lorenzo Ghiberti, the Florentine artist known for his creation of the bronze doors of the Baptistery of the Florence Cathedral, wrote the Commentari. This may be the earliest surviving autobiography by any artist. Later during this period, Tuscan painter and sculptor Giorgio Vasari wrote Lives of the Painters, recording his period’s artistic developments and the biographies of his contemporaries.

The desire and compulsion to write about the arts and artists has a long legacy. And as preeminent author of art in fiction Susan Vreeland writes, “Just as storytelling inspires art, so does art inspire storytelling.” Today’s historical novelists continue to explore the realm of the visual arts in a myriad of ways, using the verbal brush, the paint of words to bring artworks and the people and places that divined them to life for readers. This is a growing niche within historical fiction. In September 2013, on Facebook, Vreeland requested people send her titles of novels with “art tie-ins,” as she calls it. She soon amassed a list of more than 100 titles, posting many of them on her Goodreads page.

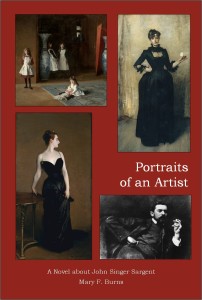

For this article I’ve interviewed eight authors of historical fiction who’ve recently written novels with art aspects: Stephanie Cowell (Claude & Camille, Crown, 2010), Michael Dean (I, Hogarth, Overlook, 2013), Cathy Marie Buchanan (The Painted Girls, Riverhead, 2013), Maryanne O’Hara (Cascade, Viking, 2012), Mary F. Burns (Portraits of an Artist, Sand Hill Review, 2013) Alana White (The Sign of the Weeping Virgin, Five Star, 2013), Donna Russo Morin (The King’s Agent, Kensington, 2012), and Susan Vreeland (Lisette’s List, Random House, August 2014, and seven other art-based novels). Here we’ll examine what compelled each author to explore the arts in their fiction, and what readers can gain by reading fiction with art threads. We are visual creatures, and for the historically curious the arts inspire unlimited ground to explore and create: storylines can include the art quest, artist and muse, plight of the female artist, artists’ biographies, the art heist, the secret messages woven into art, and onward.

In the The King’s Agent, Morin brings us “the art quest,” an artistic spin on the hero’s journey:

“It all began with my third book, To Serve a King, and my fascination with Francois I, truly the genitor of the Louvre Museum. He had art agents in all parts of Europe. One in particular, Battista della Paglia, Francois’ agent (The King’s Agent) in Italy, so captured my attention that I knew he had to have his own story. My research for these two books revealed the depth of obsession with art during the Renaissance, the noble’s fixation with acquiring it. It was extreme. Put together with Battista’s larger than life persona, and an art quest burst into my mind, begging to be told.”

“It all began with my third book, To Serve a King, and my fascination with Francois I, truly the genitor of the Louvre Museum. He had art agents in all parts of Europe. One in particular, Battista della Paglia, Francois’ agent (The King’s Agent) in Italy, so captured my attention that I knew he had to have his own story. My research for these two books revealed the depth of obsession with art during the Renaissance, the noble’s fixation with acquiring it. It was extreme. Put together with Battista’s larger than life persona, and an art quest burst into my mind, begging to be told.”

The “quest,” a classic narrative like tales of the search for the Holy Grail and the Fountain of Youth, is now infused with art by Morin.

Love, or the desire for it, is central to most of our lives. Couple this with an obsessive compulsion to create art, to be the object of and in competition with the artist’s vision, and you have the powerful, heart-wrenching drama of Cowell’s Claude & Camille, the artist and muse love story of Claude Monet and his beautiful, upper-class Parisian wife, Camille Doncieux. Cowell explains: “I am fascinated with how great art comes to be, the very messy, haphazard way things happen. The great artists of history had to deal with what we all deal with every day: love and kids and clean socks and bills, but they had, in addition, something extraordinary, and the amazing thing is, they had no idea how extraordinary it was or what it would be worth.” Nor did they have any idea, I’m sure, that their lives would become the focus of a future novelist and read by scores of doting readers.

Love, or the desire for it, is central to most of our lives. Couple this with an obsessive compulsion to create art, to be the object of and in competition with the artist’s vision, and you have the powerful, heart-wrenching drama of Cowell’s Claude & Camille, the artist and muse love story of Claude Monet and his beautiful, upper-class Parisian wife, Camille Doncieux. Cowell explains: “I am fascinated with how great art comes to be, the very messy, haphazard way things happen. The great artists of history had to deal with what we all deal with every day: love and kids and clean socks and bills, but they had, in addition, something extraordinary, and the amazing thing is, they had no idea how extraordinary it was or what it would be worth.” Nor did they have any idea, I’m sure, that their lives would become the focus of a future novelist and read by scores of doting readers.

O’Hara, author of Cascade, reveals the predicaments of a fictional female artist during the Great Depression of the 1930s: “I was originally interested in writing a short story about artists who painted for Roosevelt’s New Deal arts projects during the Depression. Then I saw a wonderful exhibit at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts: ‘A Studio of Her Own, Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940.’ I realized I wanted to write about the particular struggles of the female artist.” The female artist’s story is one that has been historically neglected; stories like O’Hara’s are changing that, elucidating the unique sacrifices and obstacles for women who pursue the fine arts.

O’Hara, author of Cascade, reveals the predicaments of a fictional female artist during the Great Depression of the 1930s: “I was originally interested in writing a short story about artists who painted for Roosevelt’s New Deal arts projects during the Depression. Then I saw a wonderful exhibit at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts: ‘A Studio of Her Own, Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940.’ I realized I wanted to write about the particular struggles of the female artist.” The female artist’s story is one that has been historically neglected; stories like O’Hara’s are changing that, elucidating the unique sacrifices and obstacles for women who pursue the fine arts.

Artist biographies make for fascinating novels, as evidenced by Dean’s I, Hogarth, which depicts the life story of eighteenth-century British painter and engraver William Hogarth. Dean notes: “Novels are about emotion. I had an instinctive emotional response to Hogarth as a man and as an artist. I also wanted to write about a man’s life-experience from birth to death. Hogarth had a very interesting life.” In Portraits of an Artist, Burns also waxes biographical with her story of American portrait painter John Singer Sargent, told by, incredibly, fifteen first-person narrators. Says Burns: “Then it hit me: the portraits would be the characters! They would tell the story of Sargent, from their point of view – each with his and her own voice – reliable or unreliable.”

by Dean’s I, Hogarth, which depicts the life story of eighteenth-century British painter and engraver William Hogarth. Dean notes: “Novels are about emotion. I had an instinctive emotional response to Hogarth as a man and as an artist. I also wanted to write about a man’s life-experience from birth to death. Hogarth had a very interesting life.” In Portraits of an Artist, Burns also waxes biographical with her story of American portrait painter John Singer Sargent, told by, incredibly, fifteen first-person narrators. Says Burns: “Then it hit me: the portraits would be the characters! They would tell the story of Sargent, from their point of view – each with his and her own voice – reliable or unreliable.”

These comments illustrate the story structures pursued, but what compels writers to choose the arts and artists as subject matter?

Vreeland explains why she has dedicated her writing career to art:

“The short answer is love. One reason I devote myself to writing about art is for me; the other is for the reader and the world. Art’s effect on the imagination is crucial to our civilization. Thanks to art, instead of seeing only one world and time period, our own, we see it multiplied and can see into other times, other worlds which offer a window to other lives. Each time we enter imaginatively into the life of another, it’s a small step upwards in the elevation of the human race. When there is no imagination of others’ lives, there is no human connection. When there is no human connection, compassion does not develop. Without compassion, then community, commitment, loving kindness, human understanding and peace shrivels.”

“The short answer is love. One reason I devote myself to writing about art is for me; the other is for the reader and the world. Art’s effect on the imagination is crucial to our civilization. Thanks to art, instead of seeing only one world and time period, our own, we see it multiplied and can see into other times, other worlds which offer a window to other lives. Each time we enter imaginatively into the life of another, it’s a small step upwards in the elevation of the human race. When there is no imagination of others’ lives, there is no human connection. When there is no human connection, compassion does not develop. Without compassion, then community, commitment, loving kindness, human understanding and peace shrivels.”

I personally believe visual art can reveal the essence of life and relay it to the masses: inspiring awe, glimpses of God, moving us to tears, striking us speechless, triggering revulsion, humbling us, or setting a smile upon our faces. Artworks and artists, historic or imagined, that attempt and produce such lofty measures, stirring such strong human emotions, are what entices me to write about the arts and artists. What compels me is the longing to enter the artist’s world, which is often obstacle-ridden, but where magic takes place, and to transmit this awesomeness and struggle to readers – to make real the experience of what it is like to wrestle in the arts, while steeped in the time period, places, and amongst the personalities that created such affecting and lasting works, to make the artists and art alive for others, for the reader to hold the paintbrush, to execute the line, to be in contact

I personally believe visual art can reveal the essence of life and relay it to the masses: inspiring awe, glimpses of God, moving us to tears, striking us speechless, triggering revulsion, humbling us, or setting a smile upon our faces. Artworks and artists, historic or imagined, that attempt and produce such lofty measures, stirring such strong human emotions, are what entices me to write about the arts and artists. What compels me is the longing to enter the artist’s world, which is often obstacle-ridden, but where magic takes place, and to transmit this awesomeness and struggle to readers – to make real the experience of what it is like to wrestle in the arts, while steeped in the time period, places, and amongst the personalities that created such affecting and lasting works, to make the artists and art alive for others, for the reader to hold the paintbrush, to execute the line, to be in contact  with the divine.

with the divine.

And as Dean poetically says, “art infuses and inspires life. Hogarth’s life, as portrayed, inspires the wider society around him. I am very visual. Music means little in my life but great art works – especially the great colourists move me. A lot.” I find this particuarly interesting, since music is the sister to the visual arts, and another creative niche within historical fiction that has been written about passionately, along with the lives of writers. I think it’s an important perspective to keep in mind because different artistic media speak to and reach different audiences.

And the final question: what can one gain by reading historical fiction about art?

“I believe stories add emotion to the artwork itself. They add breath and life…fiction infuses art with blood and bone. Such fiction explores artists as human beings with the same problems and victories we all experience,” says White, author of The Sign of the Weeping Virgin, which features an eleventh-century Italian painting at the center of a mystery. Buchanan, author of The Painted Girls, explains, “I do love the idea of readers looking at Degas’s artwork through a new lens after reading The Painted Girls, and I’ve heard from many readers that they have gone in search of his artwork and, in fact, seen it with new eyes. Readers, hopefully, gain a new appreciation for an artist’s body of work and the times in which he lived.” The benefits to readers are multifaceted and, as Vreeland insightfully writes, “I am not an art historian. I’m a storyteller. A novel reaches a different audience – an audience or a society that needs art and may not know it. That’s where I want to point my pen.”

“I believe stories add emotion to the artwork itself. They add breath and life…fiction infuses art with blood and bone. Such fiction explores artists as human beings with the same problems and victories we all experience,” says White, author of The Sign of the Weeping Virgin, which features an eleventh-century Italian painting at the center of a mystery. Buchanan, author of The Painted Girls, explains, “I do love the idea of readers looking at Degas’s artwork through a new lens after reading The Painted Girls, and I’ve heard from many readers that they have gone in search of his artwork and, in fact, seen it with new eyes. Readers, hopefully, gain a new appreciation for an artist’s body of work and the times in which he lived.” The benefits to readers are multifaceted and, as Vreeland insightfully writes, “I am not an art historian. I’m a storyteller. A novel reaches a different audience – an audience or a society that needs art and may not know it. That’s where I want to point my pen.”

Editor’s Note: Beginning this month, a weekly interview series featuring each author in this piece will be available on the Historical Novel Society website. https://historicalnovelsociety.org

About the contributor: Stephanie Renée dos Santos is a fiction and freelance writer and leads writing and yoga workshops. She writes features and interviews for the Historical Novel Society. Currently, she is working on her first historical novel, Cut from the Earth. www.stephaniereneedossantos.com

About the contributor: Stephanie Renée dos Santos is a fiction and freelance writer and leads writing and yoga workshops. She writes features and interviews for the Historical Novel Society. Currently, she is working on her first historical novel, Cut from the Earth. www.stephaniereneedossantos.com

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 68, May 2014