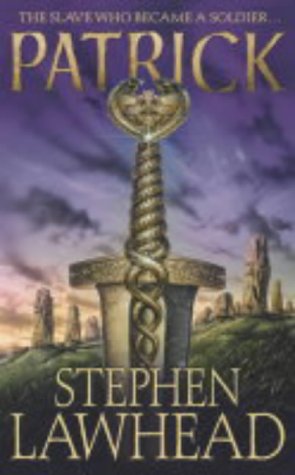

Patrick: Son of Ireland

An autobiographical narrative can create an effective historical novel, but combining this form with hagiography poses the problem of the bragging saint. Irish slave raiders capture the young Roman Briton Succat, who becomes in turn an enslaved shepherd, an apprentice Druid, a dispossessed Roman, a centurion in armies fighting the barbarians, a senator, and, finally, a missionary.

Religion plays a relatively small role for this Patrick, given to portraying himself as a military hero (“Heedless of the danger, I rode for town . . .”) or the recipient of “ardent lovemaking.” The hero-narrator can recognize the contradiction between fornication and the priesthood in others, but he never seems to reflect on the morality of his own improbable affair with a widow while he was enslaved. Stripped of religion, Patrick becomes something of an Irish nationalist, pleading to authorities that the Irish people are as intelligent as those of civilized nations. When he does embark on his mission back to Ireland, he is pursuing the Irish version of Druid Christianity, as if he is going to Eire to be converted rather than to convert.

Battle scenes where the centurion Magonus (Patrick) fights valiantly are well realized, and the scenes of Succat in slavery attempt to portray the misery that was probably the lot of most people in the ancient world. Many elements of successful historical fiction appear in this well-written novel, but the history is largely speculative and tangential while the less central parts of the legend make up much of the narrative. There is no author’s note, so one is left to wonder if the author plans a sequel showing Patrick in Ireland.