Oh, Canada!: Understanding a Nation Through Its Novels

WRITTEN BY LEE ANN ECKHARDT SMITH

My vast and rugged country is not known for having a particularly dramatic backstory. When compared to our more extroverted neighbour immediately to the south, Canada tends to be – well, quieter. This has been true from its very birth as a nation: Canada’s constitution was founded, not like the United States’ rousing declaration of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” on a somewhat more sedate promise of “peace, order and good government.” Canada gained its liberation from England, not through bloody battles in a war of independence, but via negotiation.

My vast and rugged country is not known for having a particularly dramatic backstory. When compared to our more extroverted neighbour immediately to the south, Canada tends to be – well, quieter. This has been true from its very birth as a nation: Canada’s constitution was founded, not like the United States’ rousing declaration of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” on a somewhat more sedate promise of “peace, order and good government.” Canada gained its liberation from England, not through bloody battles in a war of independence, but via negotiation.

Do not for a moment assume these foundations make Canadians merely those “nice” people you might meet on holiday. Our history is as complex and formidable as our geography. Through our historical novels, readers can gain clear understandings of the unique developments and regions that comprise Canada.

For millennia before the Vikings first established a settlement in Newfoundland (in about the year 1000) indigenous peoples lived across all of what is modern-day Canada. The arrival in 1534 of Jacques Cartier marked the beginning of the end for these nations in this territory. Joseph Boyden’s The Orenda (Hamish Hamilton, 2013) confronts the situation as it existed in the early 17th century through three contentious points of view: Bird, a warrior whose family is killed by the Iroquois; Snow Falls, the Iroquois girl Bird kidnaps in retaliation; and Christophe, a Jesuit missionary bent on converting the “brute” natives to Christianity.

The 1500s also marked the establishment of two vital industries. The fur trade and the commercial cod fishery launched exploration and white settlement from Newfoundland to the Pacific Ocean. The fur trade remained lucrative for over 250 years, and also established Hudson’s Bay Company, which is still in operation today. Fred Stenson’s award-winning adventure The Trade (Douglas & McIntyre, 2000) reveals this industry and the early days of “The Company” with all its inherent brutality. In one representative scene, a group of “stinking, bearded, ragged” traders return to a fort, where “a horse was killed and some of the blood and raw organ meat was fed to them, their teeth so loose they could only suck, not chew.” 1

During the 16th century, cod was so plentiful on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland that fishermen could lean over the sides of their boats and scoop up fish in baskets. The fishing industry sustained the Newfoundland economy – and supported several other European countries – for almost 500 years. In 1992, when the fishery collapsed, an estimated 40,000 fishermen and fish plant workers were thrown out of work. In Sylvanus Now (Penguin Books Canada, 2005) Donna Morrissey immerses readers into a 1950s Newfoundland outpost village as traditional ways of fishing are overtaken by foreign factory ships and slowly, painfully, a way of life is destroyed.

In 1608 Samuel de Champlain sailed up the St Lawrence River, scaled the north shore cliff where the river narrows, and established Quebec. This colony marked the first permanent trading post in New France and one of the first European settlements in North America. Two books open this time period for modern readers. Bride of New France (Penguin Canada, 2011) by Suzanne Desrochers describes “les filles du roi” (daughters of the King): over 800 young women who were sent to New France to populate the settlement. These women are the maternal ancestors of thousands of North Americans. Shadows on the Rock (Alfred A. Knopf, 1931) by famed American author Willa Cather depicts a year of life in 1697 Quebec for fictional apothecary Euclide Auclair and his daughter Cecile. Through them, we witness the isolation of life on “the rock,” the Catholic church’s rule, and the social structure of this precarious settlement.

The 1800s might well be themed “lost and found” for the thousands of immigrants who arrived in Canada during that century. Often lost were cultures and language; found (usually, but not always) were new opportunities in a burgeoning country. Two award-winning novels give readers diverse views into 19th-century Canada. The Jade Peony (Douglas & McIntyre, 1995) by Wayson Choy reveals Vancouver’s Chinatown and Chinese-Canadian culture from the points of view of three siblings. Their immigrant parents and grandparents helped build the Canadian National Railway, and all three generations confront what it means to live under the discriminatory Chinese Immigration Act, from the 1880s to the time of the Second World War. This Act included as one of its tenets “a white Canada forever.” Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace (McClelland & Stewart, 1996) fictionalizes the true story of Grace Marks, an Irish servant girl who, in 1843 at the age of 16, was convicted of murder. This psychological murder mystery explores the question of her guilt, which remains controversial, and provides details of daily life in Toronto and the Kingston Penitentiary.

A little-known but important piece of 19th-century Canadian history is exposed in Marie Jakober’s novel, The Halifax Connection (Random House, 2007). This tale of espionage tells the story of a Canadian agent in the American Civil War. Although Britain (and therefore Canada) was officially neutral during that war, plots were hatched by Confederates, and spies from both sides operated in centres from Halifax to Niagara Falls. Jakober also shows how the Civil War affected the very structure of Canada. In 1864 while the war was still raging, the Fathers of Confederation were beginning to hammer out the details of what would become the 1867 British North America Act, which formed Canada. The Act was designed to avoid what was seen as “the failed experiment” of the American Republic: Canada was deliberately set up with a strong central government to avoid the “sovereignty” that had allowed the southern states to secede and threaten the Union.

It’s widely acknowledged that Canada came of age during and just following the First World War. Two enduring novels provide insight into the Canadian experience from several points of view. The Wars (Clarke, Irwin, 1977) by Timothy Findley has been called “the finest historical novel ever written by a Canadian.”2 Through the main character Robert Ross, a young Canadian officer, readers experience destruction – of countrysides, of innocence, of life – and wars both internal and in France, but can also reflect on connections with animals, nature, and the sanctity of life. Hugh MacLennan’s Barometer Rising (Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1941) portrays Canada’s shift away from the influences of Britain and into a more national consciousness in the wake of the war and the 1917 Halifax Explosion – the largest man-made detonation up to that time.

It’s often said that Canadians define themselves by saying “we’re not American.” In fact, Canadians most strongly identify with the region in which they live. This is not surprising, given the immensity of the country, and some of Canada’s best-known and award-winning historical novels provide strong regional flavour. Here’s a list of titles that give readers vivid depictions of the vastly different geography in the nation, and an understanding of how the land has always shaped us.

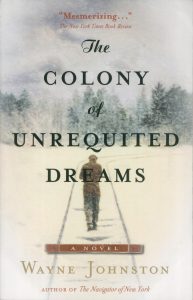

Newfoundland: Colony of Unrequited Dreams (Knopf Canada, 1998) by Wayne Johnston. This saga of hard-driving, controversial Joey Smallwood, who brought Newfoundland into Confederation in 1949, is wrapped in a travelogue that gives even those “from away” an understanding of how Newfoundland leaves an indelible mark on all who experience it.

Cape Breton: No Great Mischief (McClelland & Stewart, 1999) by Alistair MacLeod. This Canadian classic unfolds slowly back and forth between 1779 and present day, portraying through generations of the resilient MacDonald family how closely the past entwines with the present. Through the Gaelic language, through the bond of brothers, through the broken life of Calum MacDonald, MacLeod honours Cape Breton and the pull towards home.

Ontario: In Richard B. Wright’s Clara Callan (HarperCollins, 2001) two sisters struggle with living outside the boundaries of social convention and deal with the repercussions of several issues that were not talked about in Depression-era Canada. Fifth Business (Macmillan of Canada, 1970) by Robertson Davies explores themes of psychology, sainthood, myths and magic in a typical early 20th-century Ontario small town: outwardly quaint but founded on small-mindedness and rigid morality.

Prairies: In Children of My Heart (McClelland and Stewart, 1979, translated by Alan Brown) celebrated French-language author Gabrielle Roy presents a 1930s prairie village school. Immigrant children expose readers to the hardships of the prairie landscape and to the mosaic of languages and cultures they bring to the classroom – and by extension, the country.

British Columbia: Gail Anderson-Dargatz’s The Cure for Death by Lightning (Knopf Canada, 1996) is a coming of age story infused with magical realism under the shadow of World War II. In a remote farming settlement, local violence may be caused by a malevolent spirit known to the natives as “Coyote.”

Inuvik: Minds of Winter (Quercus, 2016) by Ed O’Laughlin sweeps through 175 years of polar explorers, legends, and lost expeditions. The central mystery among many in this adventure is Sir John Franklin’s failed voyage to find the Northwest Passage. The location – pack ice, whiteouts and “razor-blade air” – is where emptiness and delusion coexist with meaning and science.

Canada: as these novels attest, my nation’s history is complex, captivating and anchored in geography writ large. Although there are many more historical novels that capture other aspects of the country’s breadth and depth, may these titles be your introduction to the land perhaps best described in our national anthem: “the true north, strong and free.”

References

1. Fred Stenson

The Trade (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2000), p. 75

2. Timothy Findley

The Wars (Canada: Penguin Modern Classics edition, 2005). Quote from Introduction by Guy Vanderhaeghe.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR: Lee Ann Eckhardt Smith’s love of history and storytelling has driven her writing career. She is the author of two non-fiction social history books and magazine articles about writing engaging memoir and family history. https://www.leeanneckhardtsmith.com

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 91 (February 2020)