New Voices: Carol Cram, Lucy Pick, Kevin Montgomery & Avi Sirlin

by Myfanwy Cook

Debut novelists Carol Cram, Lucy Pick, Kevin Montgomery & Avi Sirlin have uncovered a treasure trove of hidden historical gems to inform and enlighten.

Debut novelists Carol Cram, Lucy Pick, Kevin Montgomery & Avi Sirlin have uncovered a treasure trove of hidden historical gems to inform and enlighten.

The spark that ignited” Carol Cram’s The Towers of Tuscany (Lake Union, 2014) came from her “musing one day about the Tuscan town of San Gimignano.” She writes: “On visits to Tuscany’s lovely city of towers, I was captivated by its fifteen medieval towers and commanding views over the iconic Tuscan landscape. In its heyday in the 14th century, over seventy towers pierced the blue Tuscan sky.

“So I wondered: What had San Gimignano looked like with seventy towers? This thought led naturally to another thought: Had anyone painted a view of San Gimignano with its dozens of towers? I decided to invent a painter who veered from the religious iconography prevalent at the time to paint a view of the towers of San Gimignano. My painter is a woman, because I was also intrigued by the idea of a woman painting during a period when painting was very much in the male domain.

“And then I got a sign that my novel was destined to be written. I stumbled upon the website for San Gimignano 1300, a museum in San Gimignano that includes a large scale model of the city in the year 1300, complete with all seventy of its towers. On my research trip to Italy, the morning I spent at San Gimignano 1300 was one of the most productive of my writing career to date.

“The Towers of Tuscany is the first of a planned series of three historical novels with an ‘arts twist.’ The second novel, A Woman of Note, tells the story of a woman concert pianist and composer in Vienna in the late 1820s and will be published in 2015. The final novel, Upstaged , combines the story of an actress caught up in the ‘Old Price Riots’ at London’s Covent Garden Theatre in 1809 with the efforts of an abolitionist to end slavery.”

Avi Sirlin’s biographical historical novel The Evolutionist (Aurora Metro, 2014) was not inspired by a place as in the case of Cram’s novel, but by a book. He explains: “[My] early academic background was in biology, and I first read about Alfred Wallace around 2001 in a remarkable scientific book, Last Song of the Dodo by David Quammen. At the time, I thought: Wallace sounds like an interesting fellow, so I wonder why I haven’t heard of him before? Then I largely forgot about him.

by a place as in the case of Cram’s novel, but by a book. He explains: “[My] early academic background was in biology, and I first read about Alfred Wallace around 2001 in a remarkable scientific book, Last Song of the Dodo by David Quammen. At the time, I thought: Wallace sounds like an interesting fellow, so I wonder why I haven’t heard of him before? Then I largely forgot about him.

“Flash forward to late 2010 when I’d just finished reading an historical novel and got to wondering about the author’s choice in deciding to write about that particular individual. I started pondering whether there was any historical figure who sufficiently intrigued me to devote writing a novel about him or her. In a flash—I swear, it was less than a second—even though I hadn’t thought of him in the longest time, Wallace just popped up.

“My initial reaction was that I knew next to nothing about him, that I’d probably heightened in my mind his importance, and that if I did a little digging, I was sure to find he wasn’t as interesting as I’d like to believe. So I did some quick research and found quite the opposite: Wallace proved absolutely compelling.

“Soon I was immersed in biographies and anthologies, as well as Wallace’s autobiography, travel narratives and scientific essays. From all that had been written, and despite the very public nature of his work, I was fascinated to find Wallace was an intensely private man with strong external contradictions. Also, that he’d achieved considerable fame during his lifetime and that his scientific, albeit not public, legacy remained vast. I wanted to learn more about him, bring out his inner life, especially those contradictions, and raise public awareness of this intriguing, largely obscured personality.”

Lucy Pick, author of Pilgrimage (Cuidono, 2014), points out that: “A lot of my readers know that image on the cover of my novel, Pilgrimage, is a detail from a painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, a polyptych (that is to say, a panel painting that folds up) that had once been an altarpiece. The altarpiece as a whole is quite incredible, and shows scenes from the life (and death) of Saint Godeleva; in my novel, the mother of my heroine, Gebirga. The panel even includes images of the blind daughter who inspired Gebirga, so I was delighted to be able to use a part of it for the cover.”

Lucy Pick, author of Pilgrimage (Cuidono, 2014), points out that: “A lot of my readers know that image on the cover of my novel, Pilgrimage, is a detail from a painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, a polyptych (that is to say, a panel painting that folds up) that had once been an altarpiece. The altarpiece as a whole is quite incredible, and shows scenes from the life (and death) of Saint Godeleva; in my novel, the mother of my heroine, Gebirga. The panel even includes images of the blind daughter who inspired Gebirga, so I was delighted to be able to use a part of it for the cover.”

However, this was not the inspiration for her novel, which came from a quest to answer, she says, “two questions that combined to create a single ‘lightbulb’ moment of inspiration. I am an academic historian, and one of my favourite listservs about medieval history used to have a ‘saint of the day’ feature. One July 6th, the story was all about Saint Godeleva, patron of battered wives, named as such because her husband had her murdered. I then discovered a late medieval legend about Godeleva – that after killing his wife and founding the monastery, her husband had gone off on crusade to expiate his crime, and also that he had a daughter who was stricken blind because of his actions. The panel painting that we used for the cover of the novel depicts that late legend.

“What would it feel like, I wondered, to have a saint for a mother, who cured everyone except for you? That was my first question. The second came from a manuscript called the Codex Calixtinus. This manuscript is a 12th-century compilation of texts about the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, in Spain. Its most famous section is a ‘Pilgrim’s Guide,’ which describes the stages of the route and all the saints and shrines one would encounter on the way, much like a modern travel brochure. This manuscript contains a colophon that describes its unusual origins. It reads: ‘The Poitevin Aimery Picaud of Partheney-le-Vieux and Oliver d’Asquins and their friend Gebirga of Flanders gave this book to Saint James of Galicia for the redemption of their souls.’ Now, our best guess is that this manuscript had several authors, and Aimery Picaud, whoever he was, was its compiler. Who then was Gebirga of Flanders, and how did an unknown laywoman become important enough to have her name mentioned in this work?

“That was my second question. And then, the light went on – Gebirga of Flanders became the blind daughter of Saint Godeleva, and I knew I had a story.”

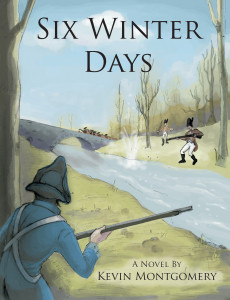

Kevin Montgomery’s flash of inspiration for Six Winter Days (Blue Water Press, 2014) came from his interest in history, “especially obscure American battlers.” So, he says, having “read yet another non-fiction account of the battles of Trenton and Princeton that devoted only a single paragraph to the battle of Trenton-Two,” he set out to explain the battle and its significance. As Montgomery states, he “originally wrote it as a screenplay, because I enjoyed Mel Gibson’s movie, The Patriot. In a screenplay you don’t have to provide a lot of details, in which Trenton-Two is pretty skimpy. However, I wasn’t satisfied with that writing, so I decided to try it as a novel. Also, Hollywood often likes to kill their main characters, so when I opted to only wound my hero, I felt better.” His story is “about two teenage brothers who walk westward from Princeton, New Jersey. They’re trying to get to Allentown because their mother wants them to get away from the war. In the middle of their journey, they stumble straight into the battle of Trenton-Two, so now I had to describe that battle. I plotted the location of all the characters and troops against time and distance based on the limited information I had from non-fiction accounts.

from his interest in history, “especially obscure American battlers.” So, he says, having “read yet another non-fiction account of the battles of Trenton and Princeton that devoted only a single paragraph to the battle of Trenton-Two,” he set out to explain the battle and its significance. As Montgomery states, he “originally wrote it as a screenplay, because I enjoyed Mel Gibson’s movie, The Patriot. In a screenplay you don’t have to provide a lot of details, in which Trenton-Two is pretty skimpy. However, I wasn’t satisfied with that writing, so I decided to try it as a novel. Also, Hollywood often likes to kill their main characters, so when I opted to only wound my hero, I felt better.” His story is “about two teenage brothers who walk westward from Princeton, New Jersey. They’re trying to get to Allentown because their mother wants them to get away from the war. In the middle of their journey, they stumble straight into the battle of Trenton-Two, so now I had to describe that battle. I plotted the location of all the characters and troops against time and distance based on the limited information I had from non-fiction accounts.

“Then in my first draft, I got to the Battle of Princeton. I had always thought that I understood that battle fairly well, but laying it out was a difficult task. In non-fiction, you tell what happened. As a fiction writer, you have to tell not only what happened, but also why, and I couldn’t figure out why British Colonel Mawhood didn’t see the Americans in his rear.” So having wracked his brain he: “read everything about the battle. No historian explained it. I went over my maps, calculating the locations of the troops. I moved them around. Maybe somebody was wrong. No, nothing worked. I even looked at the weather. Maybe it was too dark or something, but paintings of that battle showed nothing significant.

“Finally I said to myself, ‘Where was the sun?’ That did it. I plotted the location of the sun and that worked. Five variables had to come into exact play in order to explain the problem: the location of Mawhood (he couldn’t have been where historians said he was), the weather (it had to be clear, not like the paintings), the location of the sun, the topology of the land, and the time of day.”

What is considered as an inspirational gem by one author will not have the same allure for another. Fortunately, every author of historical fiction will seek and uncover the places, ideas, characters and historical epochs that are attractive to them. The debut novelists Cram, Pick, Montgomery and Sirlin have unearthed unusual treasures to share with their readers and to illuminate less well-known episodes in history.

About the contributor: MYFANWY COOK would love for you to tell her about any exciting debut novelists you discover. Please do email (myfanwyc@btinternet.com) or tweet (twitter.com/MyfanwyCook).

______________________________________________

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 71, February 2015