Marie Curie’s Many Lives: Jillian Cantor’s Half Life

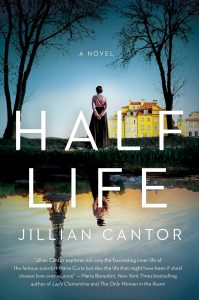

Jillian Cantor’s novel Half Life (Harper Perennial, 2021) is the story of scientific pioneer Marie Curie, whose discoveries about radioactivity led to a Nobel Prize. Curie was the first woman to be awarded the prize and is still the only woman to win it twice. But the novel is also the story of another woman, another version of Marie: an imagined woman named Marya who might have existed, had history played out differently.

Jillian Cantor’s novel Half Life (Harper Perennial, 2021) is the story of scientific pioneer Marie Curie, whose discoveries about radioactivity led to a Nobel Prize. Curie was the first woman to be awarded the prize and is still the only woman to win it twice. But the novel is also the story of another woman, another version of Marie: an imagined woman named Marya who might have existed, had history played out differently.

Marie Curie was born Marya Sklodowska in Warsaw in 1867. In 1891 she was engaged to a budding mathematician named Kazimierz Zorawski but, due to the clashing economic status of the two, his parents forbade the marriage. Heartbroken, Marya left Poland for Paris, where her older sister was living. There, she began to study chemistry and physics. She adopted the name Marie, met Pierre Curie, and the rest, as they say, is history. Cantor’s novel asks a captivating question: what if Marya had stayed in Poland and married Kazimierz? What would her life have been like? For Cantor, this point in Curie’s life is a way in to thinking about larger ideas of fate and agency. She notes, “I think we all make choices in our lives, small and large, all the time, and these choices send our lives and our futures in certain directions. It’s always kind of fascinating to consider the what-ifs. But I also always wonder if there are some things and people in our lives that are maybe meant to be no matter what choices we make.”

This idea of ‘meant to be’ plays out through the novel’s structure. The story is written from the points of view of both Marie and Marya, each chapter alternating between them and covering the same time periods so that the reader experiences two versions of one woman’s life in tandem. Cantor refers to this as a “puzzle” to write, but a hugely enjoyable one: “I loved the way I could have elements echo in both storylines, only in slightly different ways. This was actually one of my favourite parts of writing the story this way – having Marie and Pierre ride bicycles together or walk along the water in Sweden or hike in Zakopane, or having Marie and her sisters visit the beach, but having the scenes play out differently as an echo in the opposite timeline. It was a really challenging and fun writing exercise to consider the way the same scene would take on a very different meaning because of point of view and how the characters’ choices had changed them in one storyline versus the other.”

Characteristics of the historical figure at the heart of the story also had a part to play in working out the novel’s structure, as Cantor makes clear: “What inspired me was looking at how her real life was filled with so much career success, but also offset with this deep personal tragedy, again and again. Marie was very logical, very much a scientist, in every aspect of her life. So I imagined she would always believe that her choices, her actions, should lead to very specific reactions. It felt right for her character, that she would want to believe she had ultimate control in this way, to choose everything she wanted.” In Marya’s fictionalised narrative, the reader sees how a single choice made differently could alter so much.

The form of the novel didn’t present it itself immediately, and Cantor had two false starts, first with a “straight biographical/historical novel about Marie’s life” which faltered fifty pages in, and then a second attempt which told the story of Marie’s daughter Ève but which also failed to fire. The solution came from a “tidbit” of information Cantor had come across early in her research for the novel but had been unsure what to do with. The real-life Kazimierz, who Marie had left behind in Poland after his family insisted their engagement be called off, is reported to have spent the last years of his life outside the Radium Institute in Warsaw, staring at the statue of Marie Curie erected there. This resonant image stuck with Cantor as she worked on the earlier versions of the story: “In all that time in my mind I kept coming back to that one detail about Kazimierz, staring at the statue of Marie, and wondering how I could incorporate that into my story. Six months and two false starts later, it finally occurred to me that this tidbit was actually the key to the story I really wanted to tell. And so, I started the book over for the third time, in the parallel timelines that exist now”.

The effect of the parallel timelines is to provide an alternate history of Marie Curie, one which offers the reader another way of understanding this famous historical figure. This approach is one Cantor has been drawn to in previous novels: “I’m always very interested in the way point of view can shape or change a story. In The Hours Count, for instance, my character is a fictional neighbour of Ethel Rosenberg, and so I got to reimagine her real story through the eyes of my fictional protagonist. Margot allowed me to explore the point of view of Anne Frank’s sister, and imagine how it might’ve been different than the story we all know in Anne Frank’s diary. And in Half Life, I was able to explore the world from two very different versions of Marie Curie at once, considering how the world would’ve looked and been different in each perspective.’

If the ‘straight’ historical novel offers the reader untold stories, bringing to light the over-looked and under-played to give a fresh perspective on real events, then perhaps the ‘alternate history’ historical novel achieves something else – all the delights of historical fiction matched with an uncanny, fruitful plurality.

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR: Katherine Stansfield’s latest historical crime novel, The Mermaid’s Call, set in Cornwall in 1845, is out now. She is also one half of the fantasy crime-writing duo D. K. Fields.

Published in Historical Novels Review | Issue 96 (May 2021)