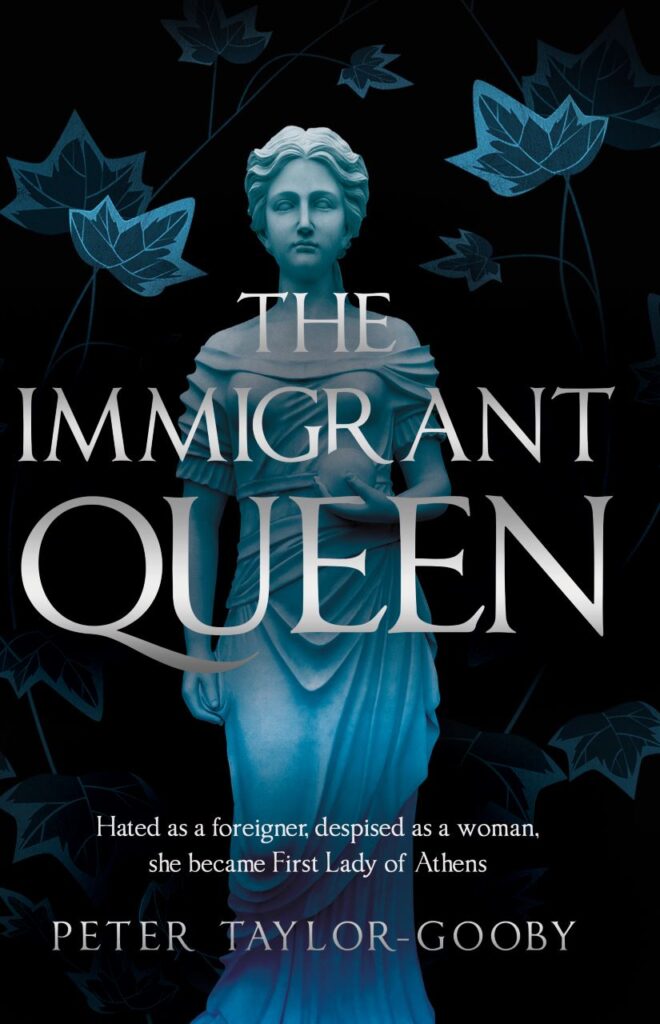

Launch: Peter Taylor-Gooby’s The Immigrant Queen

INTERVIEW BY ELLEN IRWIN

Peter Taylor-Gooby loves walking, cycling, writing and talking to his children. He has worked on adventure playgrounds, in a social security office, as a teacher, as an academic and for the local food bank. He used to think that academic work was the way to understand issues that matter. Now he realises that you have to engage with compassion, love and pain – and that means novels.

How would you sum up The Immigrant Queen in just one or two sentences?

They ignored me as a woman and despised me as a foreigner, but they had to respect me for who I was. Then I married the man I loved and became First Lady of Athens.

How did you discover your heroine, Aspasia? What was it about her that begged you to write her story?

How did you discover your heroine, Aspasia? What was it about her that begged you to write her story?

Aspasia was a remarkable woman who lived an outstanding and passionate life. At school I was taught simply that she was the wife of Pericles and the mother of one of his children. It was only much later when I started to think about equality in ancient Athens and realized that we have the names of thousands of men and the stories of hundreds, but for women we only have the names of a couple of hundred, mainly as wives and mothers, and the stories of fewer than fifty. Then I knew Aspasia’s story had to be told. She was not only a woman, but also an immigrant. Many Athenians hated and despised immigrants, yet she gained the highest position for a woman in Athenian society and left her mark on philosophy and on politics. How did she succeed? What drove her? I wanted to find out and I could only really do so by writing her story for myself.

Pericles was reputed to be spellbound by Aspasia. What do you admire about her? What do you think she could teach people living in our modern world?

She didn’t give up. There were many challenges in her life but she didn’t let them stop her.

She was a major intellectual as well as a beautiful and passionate woman. It must have been hard to gain acceptance, but she was the only woman invited to join Socrates’ circle and to debate with him. She wrote philosophical dialogues which have been lost but are quoted by writers such as Xenophon. A number of commentators report that she wrote Pericles’ most famous speeches and acted as a political advisor to him. She had a great deal to contribute and she knew her worth.

What interested you about fifth-century Athens as a backdrop for your novel?

It was such a contradictory city: successful, wealthy, a democracy (for male Athenians) and culturally advanced, producing plays, philosophy and histories that are still read. But it was desperately unequal. Slaves were treated in an appalling way, many imprisoned underground in the silver mines for all of their short lives. Women were simply not recognized as equals or as citizens and almost all lacked any education and had no access to the cultural riches of the city. Immigrants were treated with suspicion, forced to pay high taxes and subject to expulsion. In some ways it was a world a little bit like ours. Aspasia was both a woman and an immigrant and triumphed against many obstacles. I really wanted to show her story and, through other characters, such as the slaves Limander and Pelion and the women whom the male characters simply ignore, to help people understand what the reality of life in Athens was for so many.

In addition to writing this novel (as well as novels Ardent Justice and The Baby Auction), you have been widely published in your career as a professor of social science working towards social policy change. How has your professional work impacted your interpretation of Aspasia’s life as both an immigrant and a woman in ancient Athens?

I used to think that our society would grow more equal and generous as we became richer and better educated. That has not happened. Women do not have the same opportunities or rewards as men. Perhaps it needs outstanding individuals to force the pace of change. Aspasia knew she could write dialogues that the men around her wanted to read and that she was the equal of any man. I wanted to show how she confronted the challenges that faced her and maybe learn something about how exceptional people can triumph against obstacles similar to those we face in the present day. Aspasia at one stage ran an academy for women to teach them in the way that Plato and Aristotle taught men. Perhaps she has something to teach us.

Did you have any other profound realizations about the impacts of social inequality that you wanted to reflect in your story as you were researching for this novel?

Aspasia was an outstanding figure. Others were not so successful. I include the parallel tale of Limander, an intelligent and talented man but a slave, unable to live the life he so passionately desires or to be with his lover because of his lowly status.

What drew you towards writing historical fiction after being so widely published in the academic sphere?

I’ve always wanted to write fiction. Academic research draws on facts: statistics, reports and surveys. I wanted to create novels that engaged people’s passions and desires, the feelings that really drive our lives.

What writing advice would you like to share with aspiring authors?

Write! Don’t be frightened to throw it away and write some more. If you’re aiming for a novel, try short stories to understand the characters, their relationships, ambitions, desires and challenges.

What is the last great book you read?

Claire Keegan’s Small Things Like These: simple, direct and immensely powerful. But maybe I should say the Iliad, which I also read recently.

HNS Sponsored Author Interviews are paid for by authors or their publishers. Interviews are commissioned by HNS.

![]()